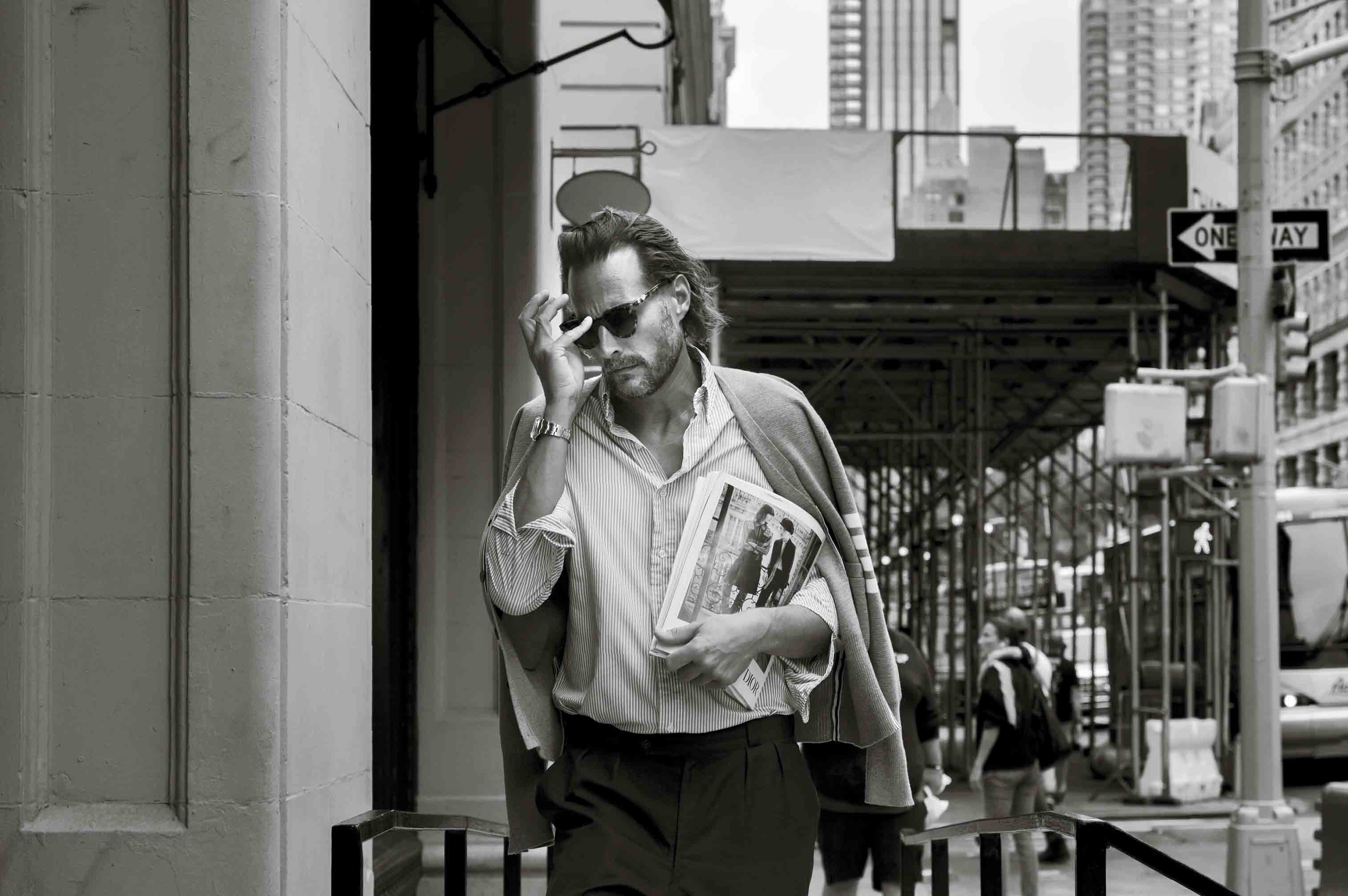

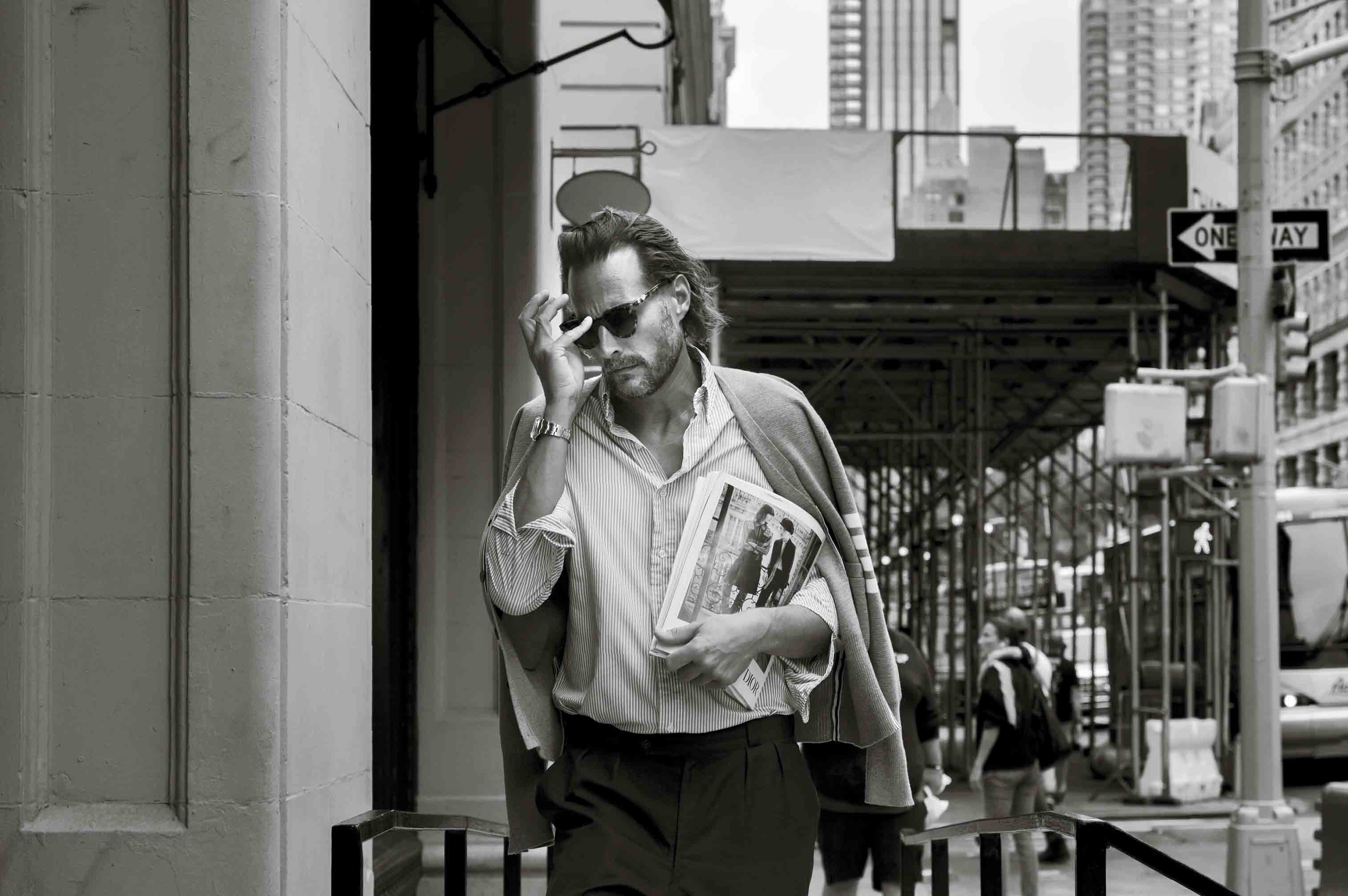

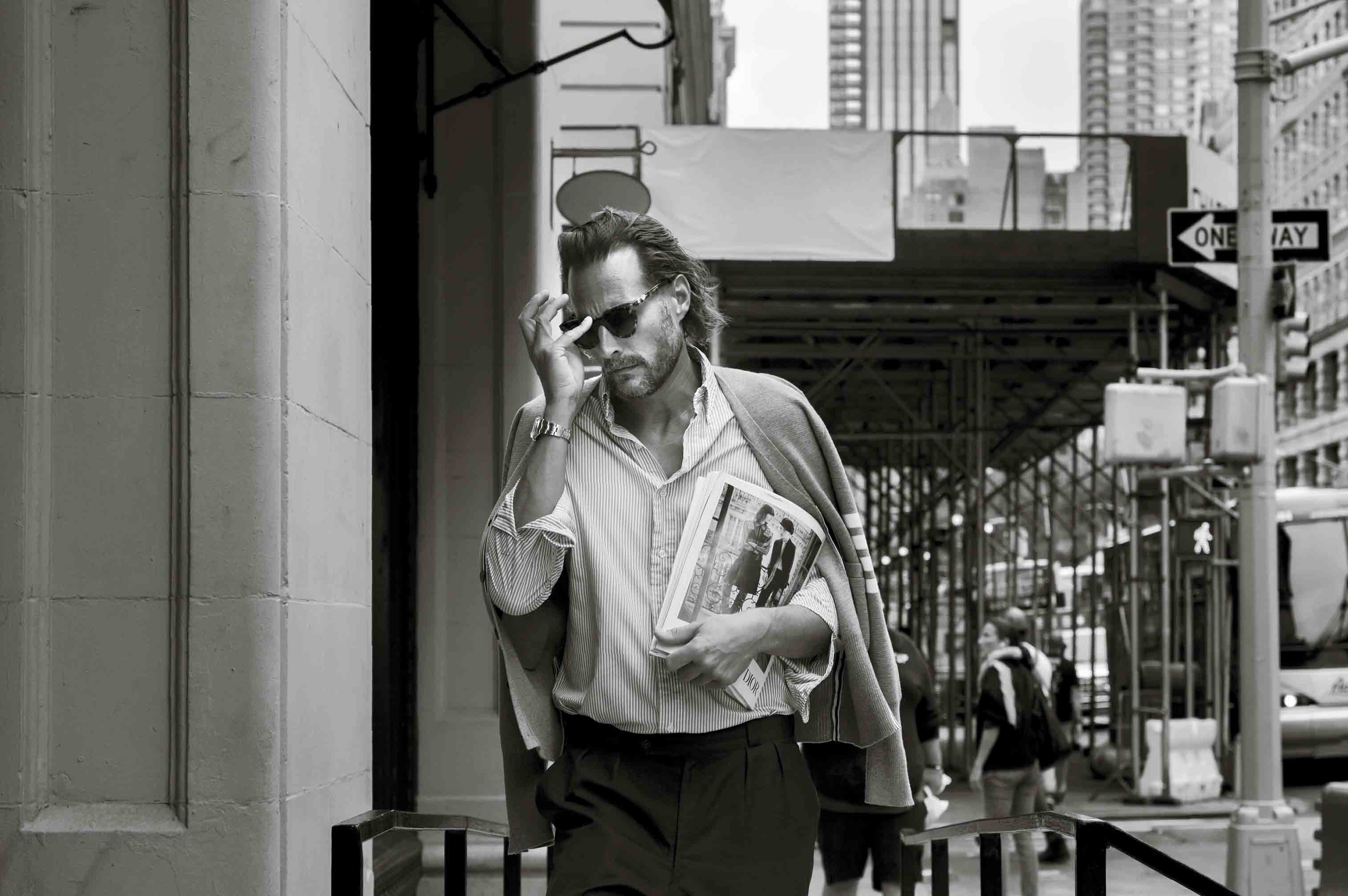

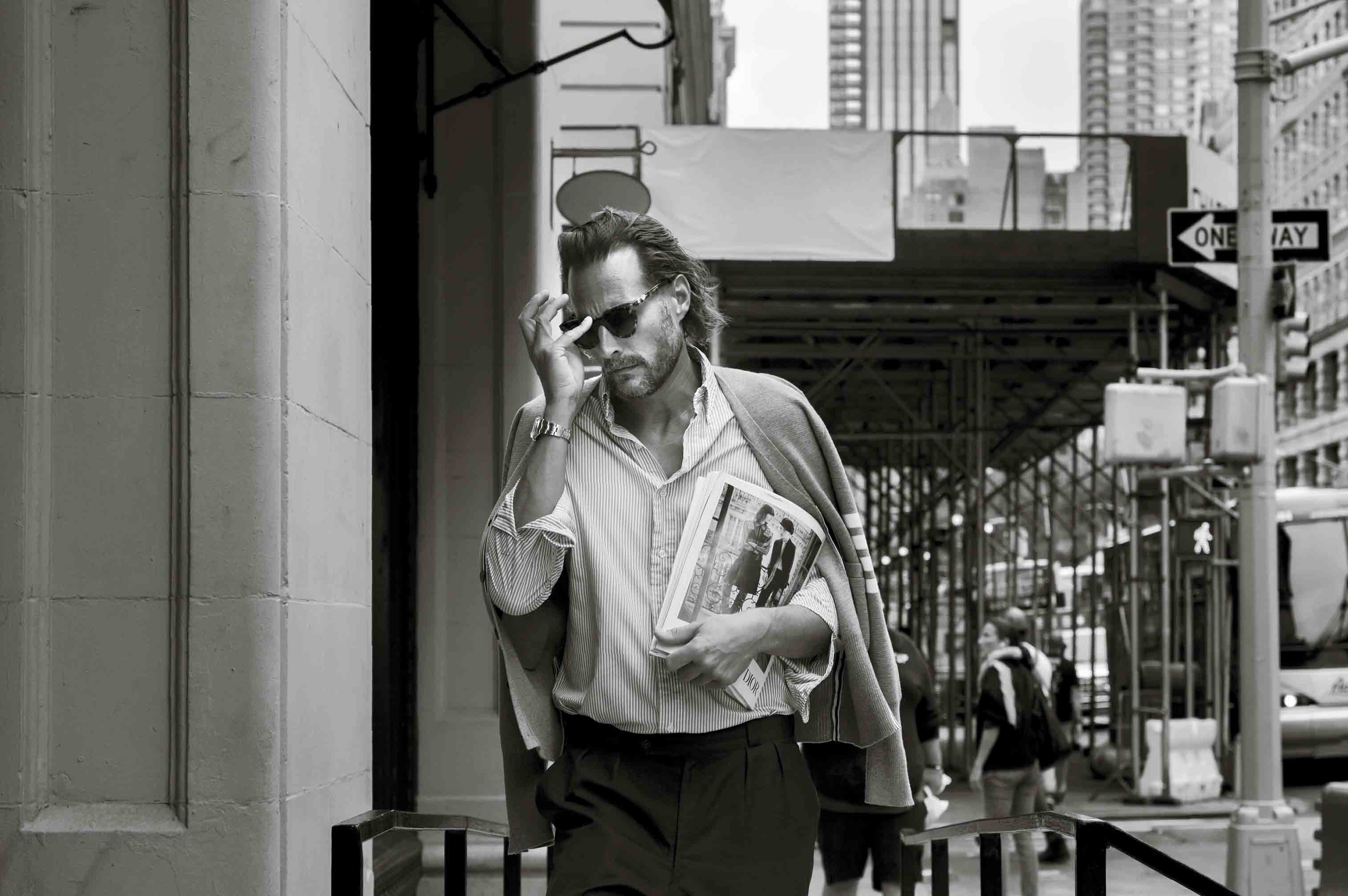

SUMER

short film

( fragment )

Script: Arthur Larrue

Video, sound: Óscar Monzón

Voice: Victoire de Lencquesaing

SUMER short film (fragment)

SUMER short film (fragment)

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER

Óscar Monzón

& Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón

& Arthur Larrue

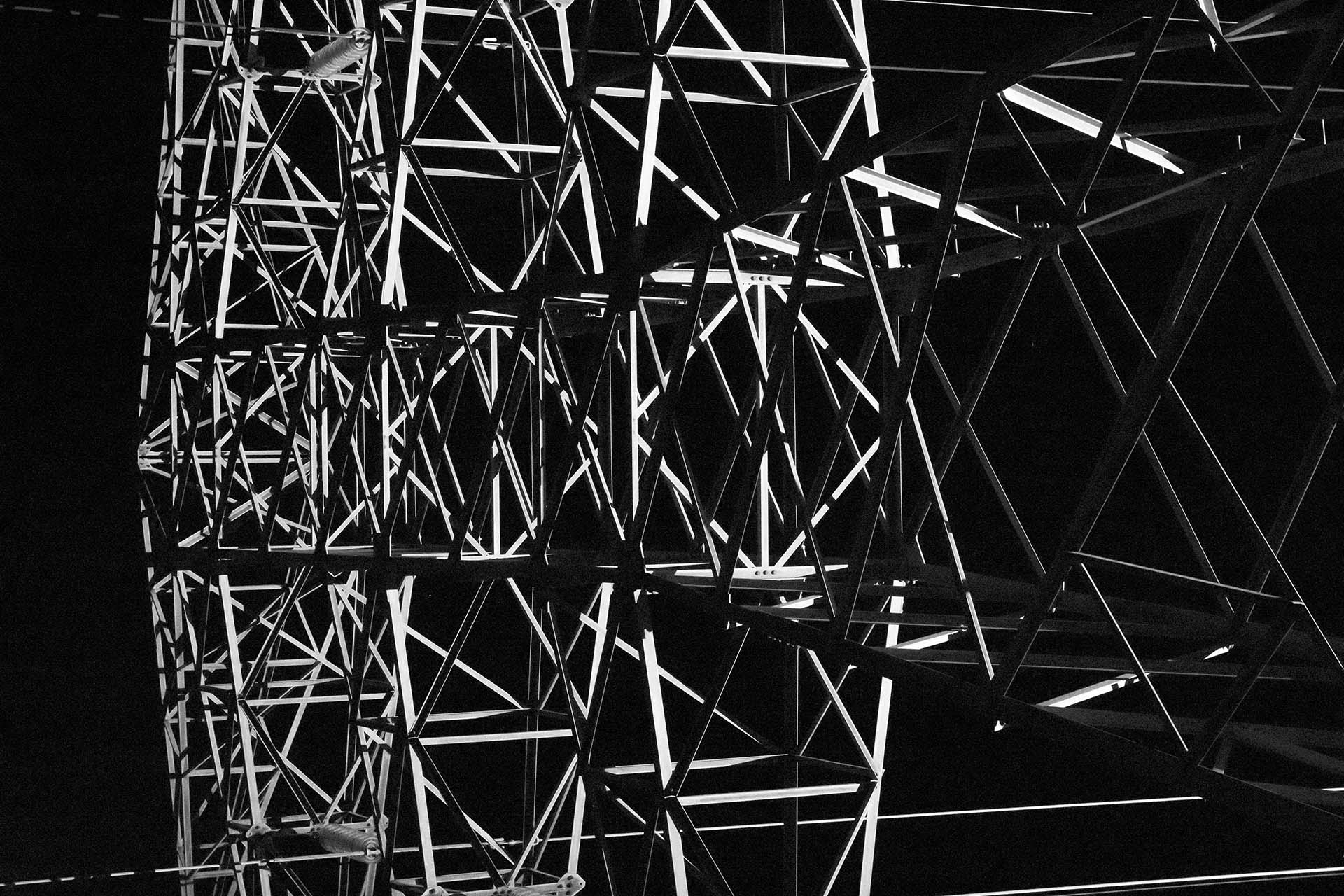

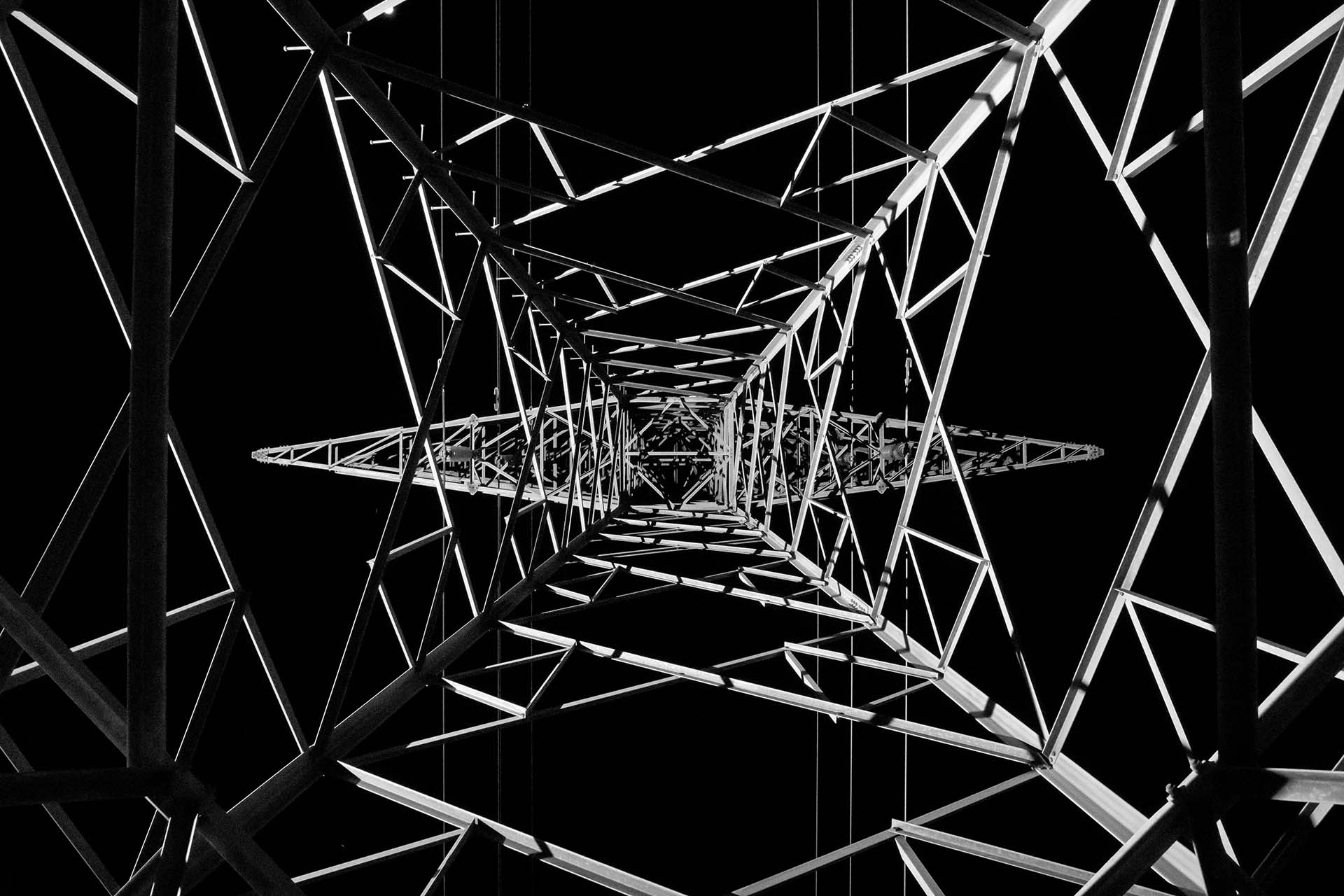

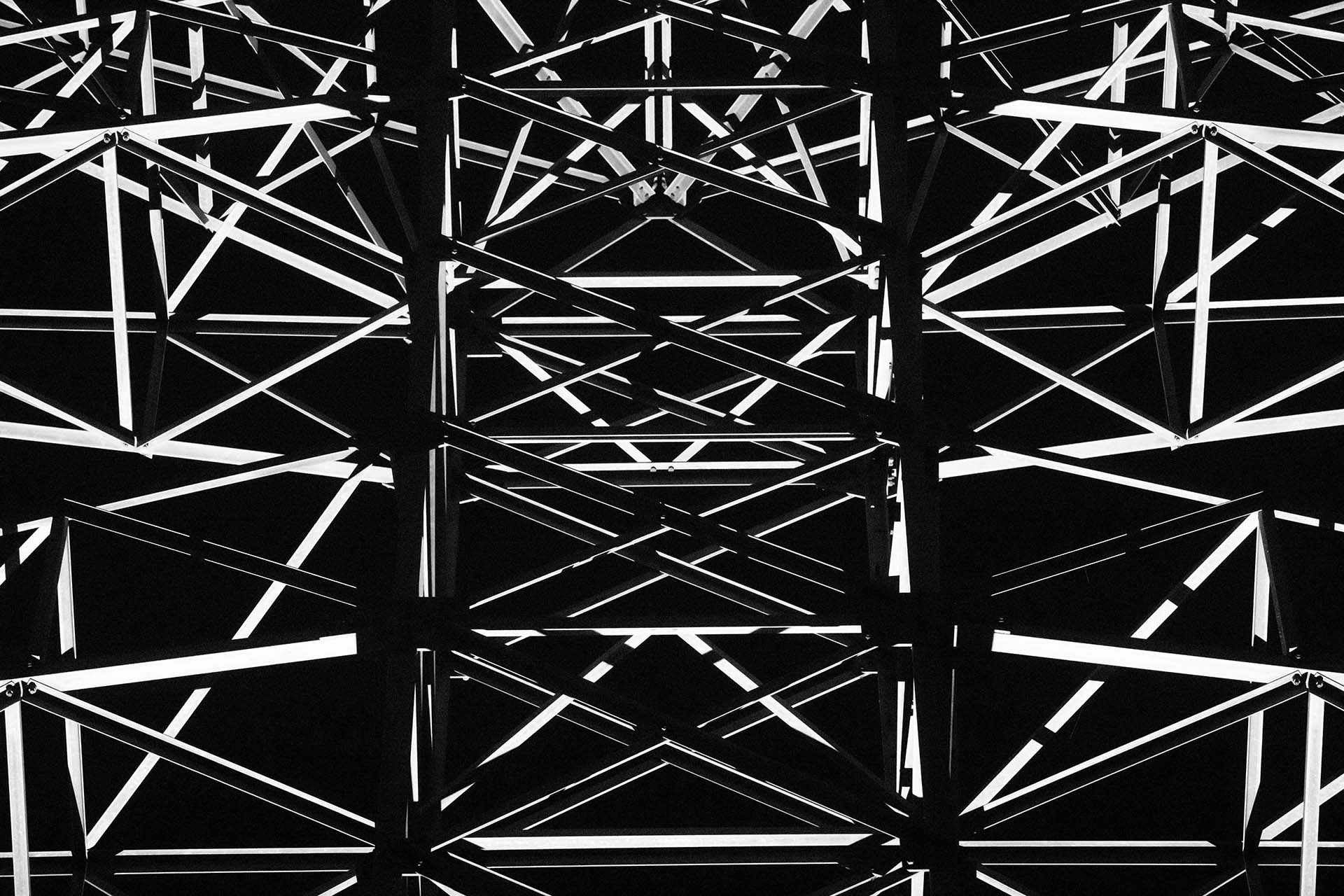

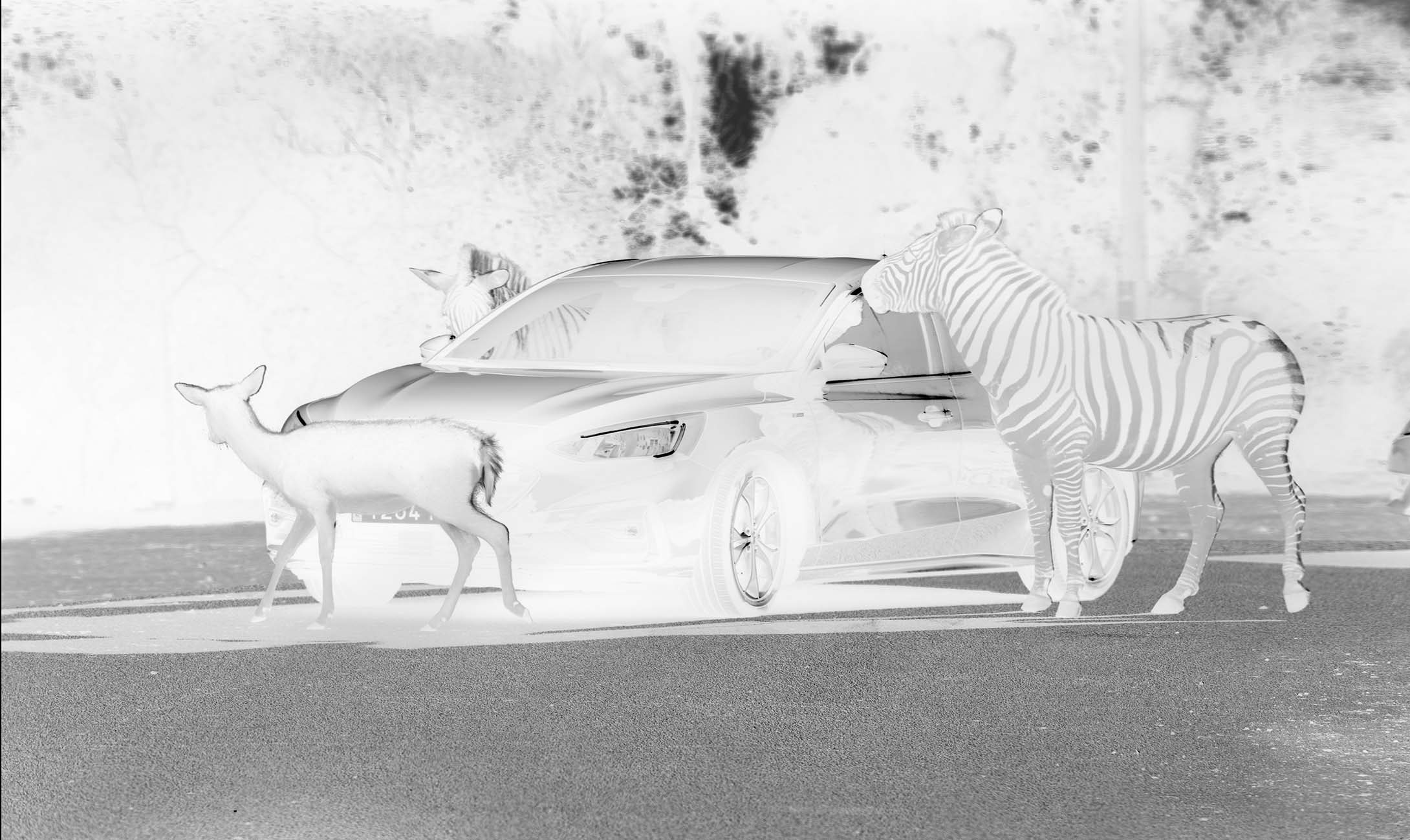

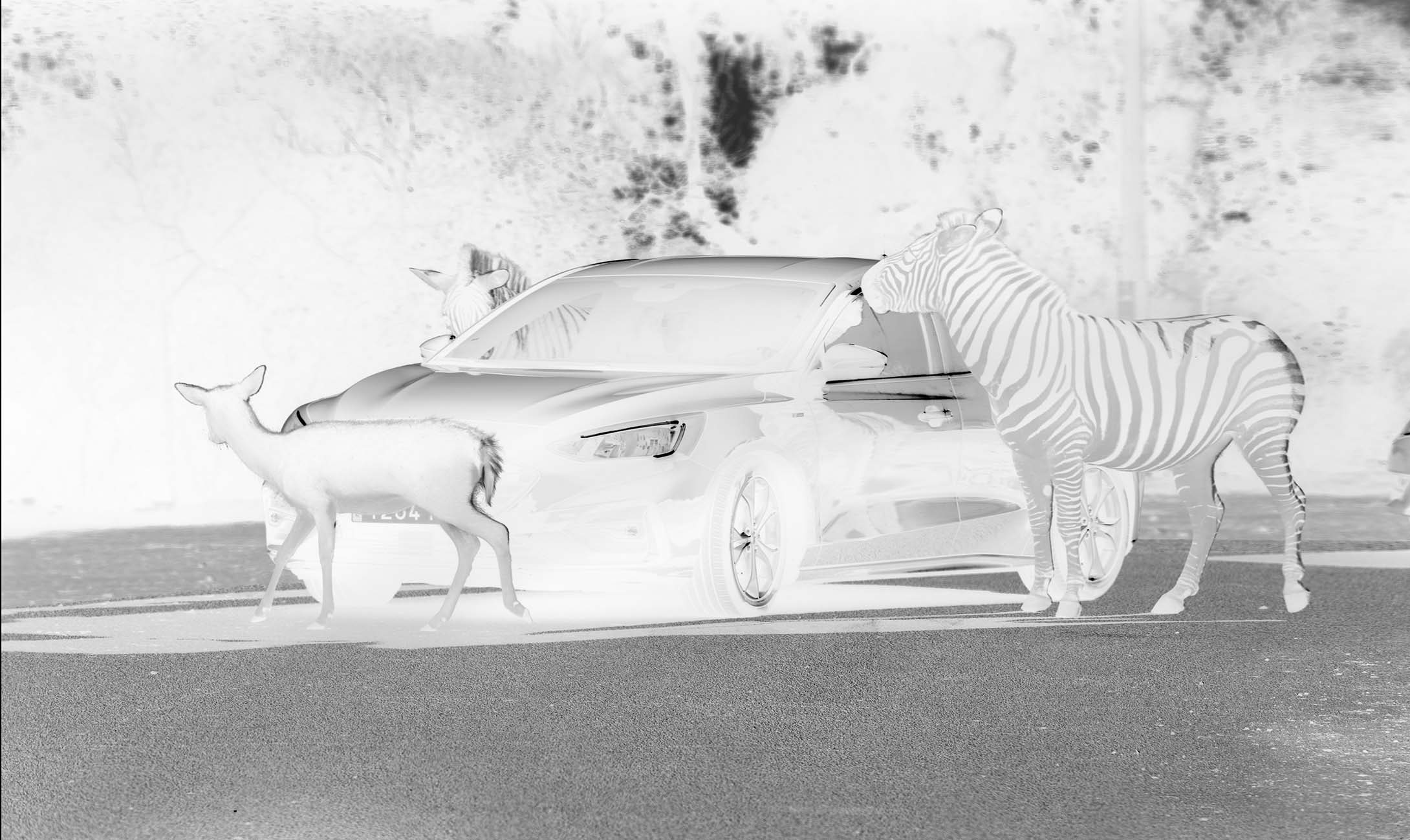

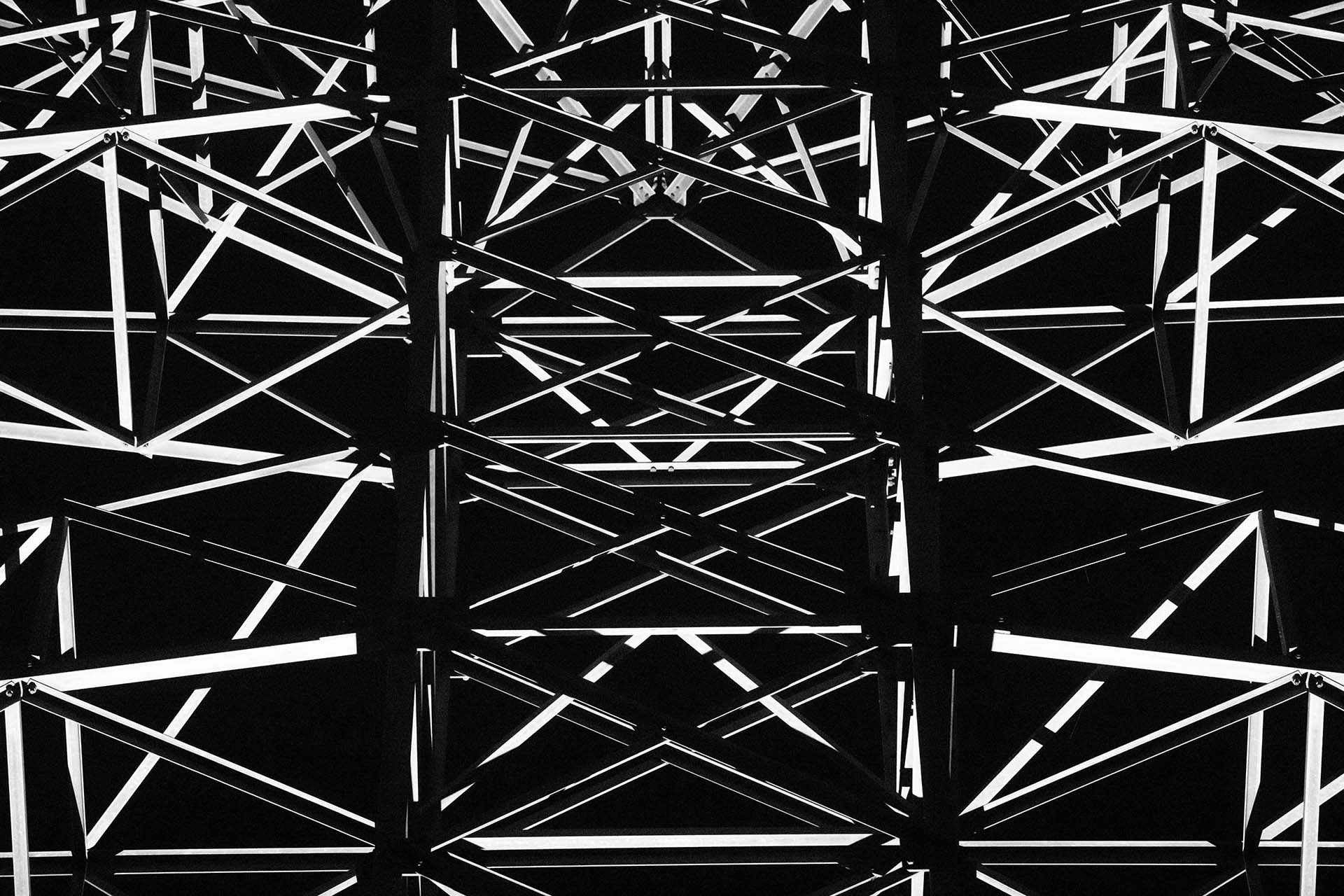

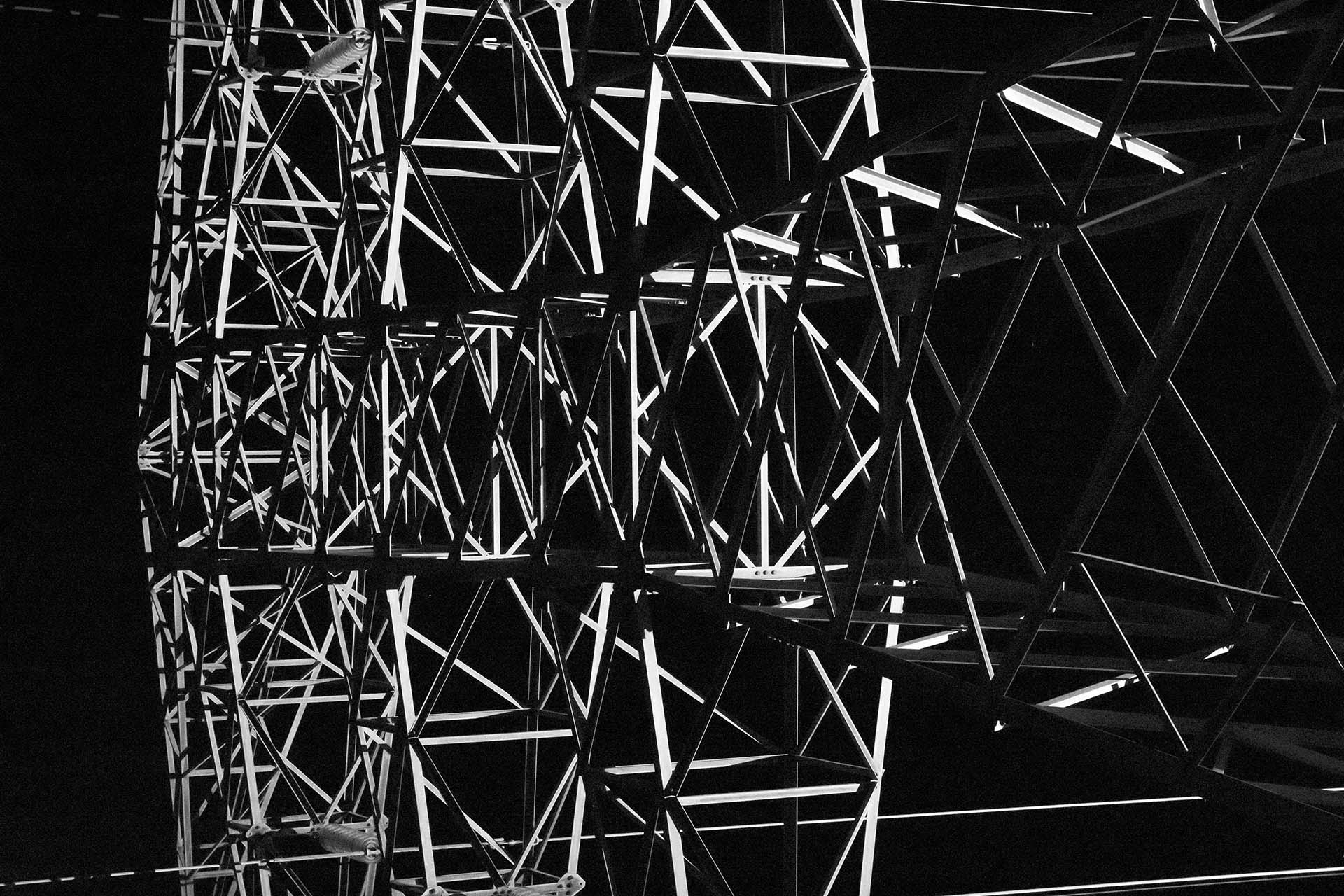

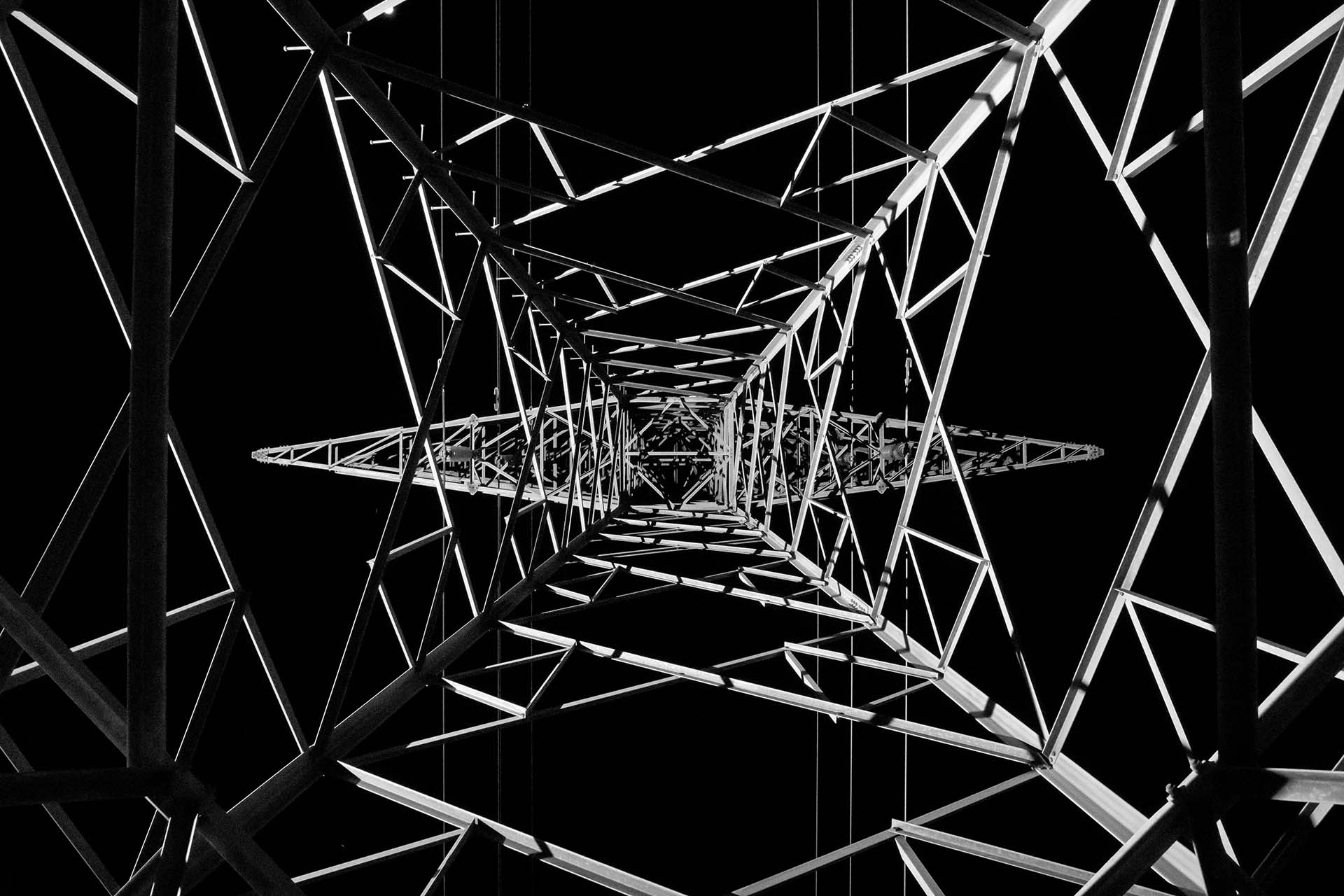

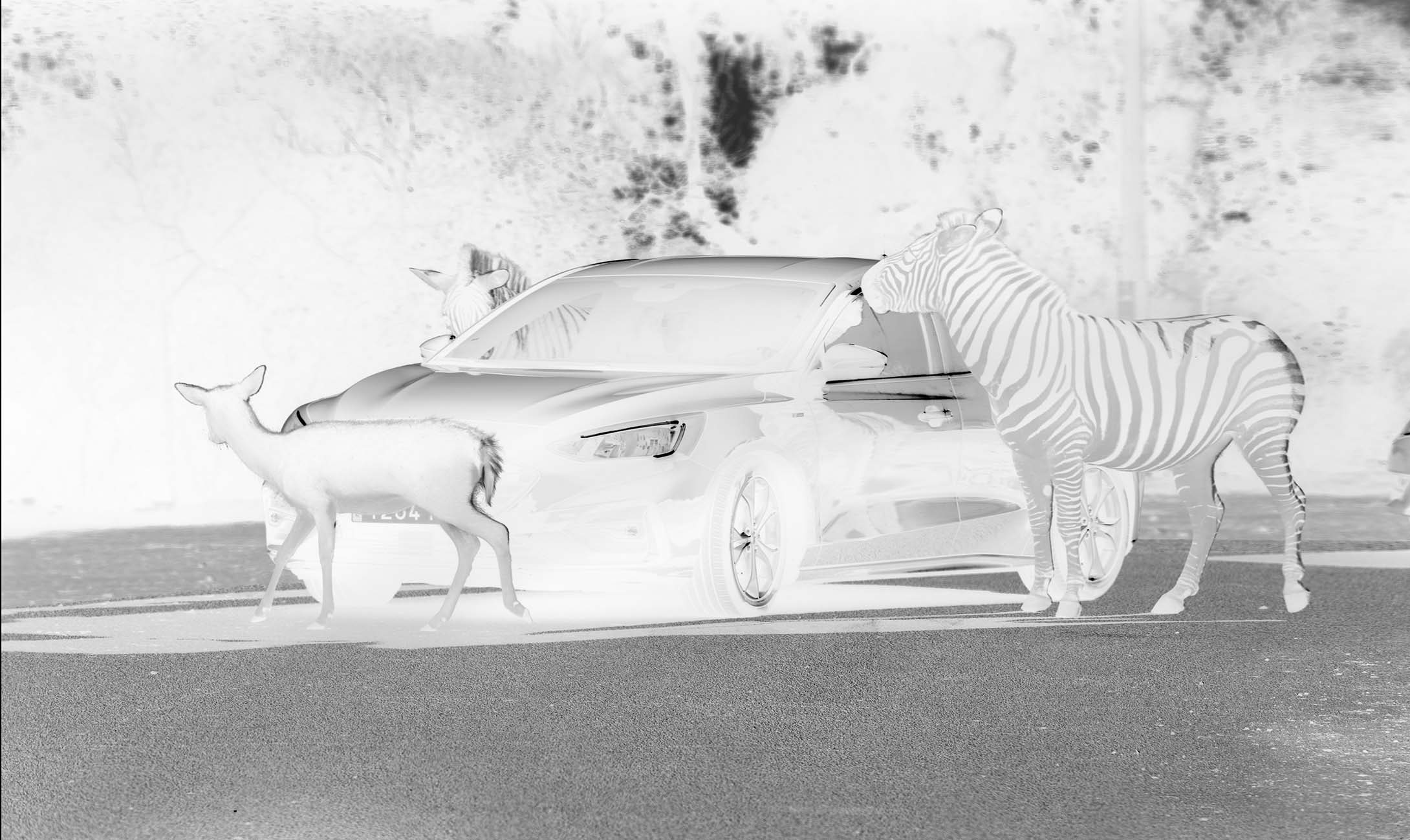

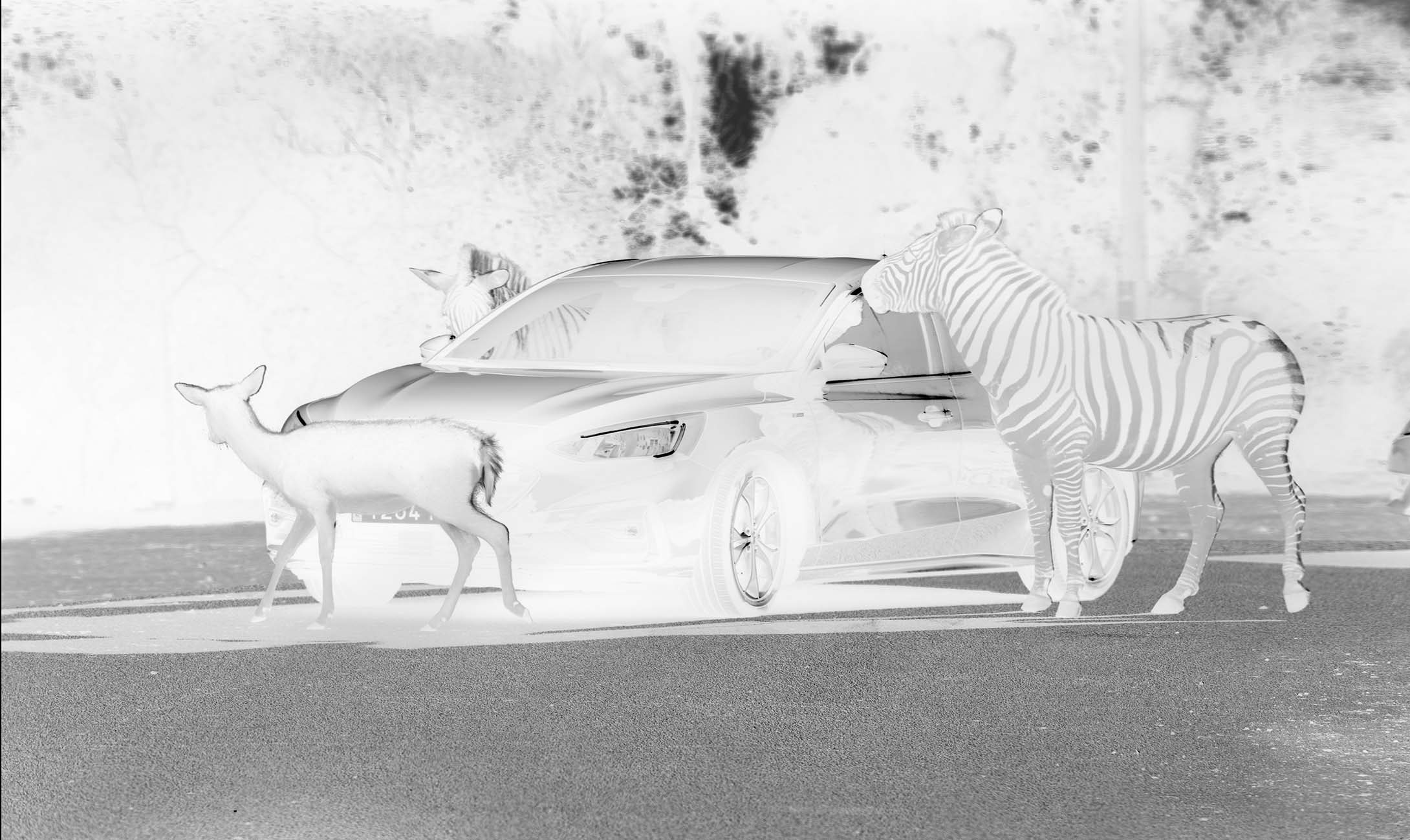

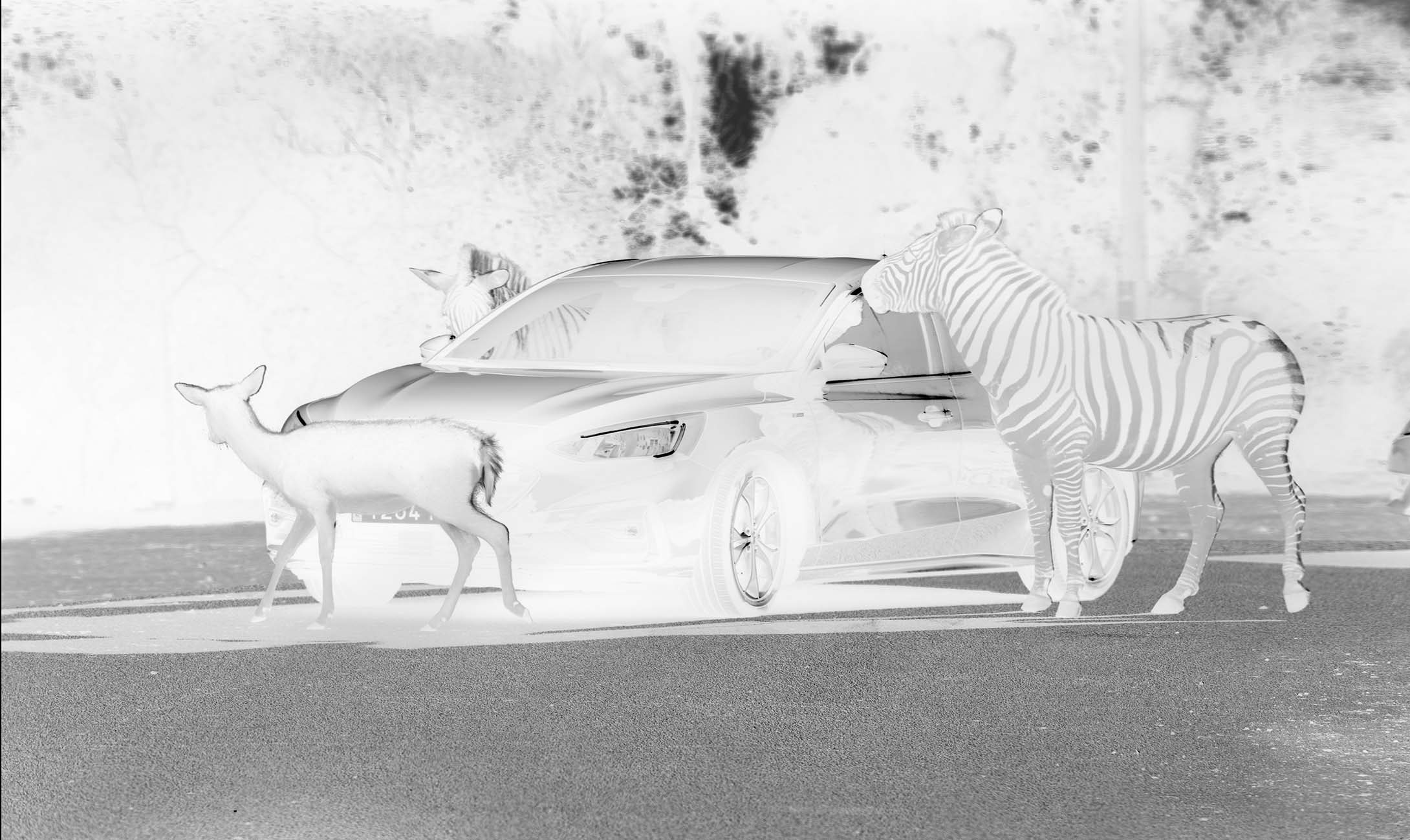

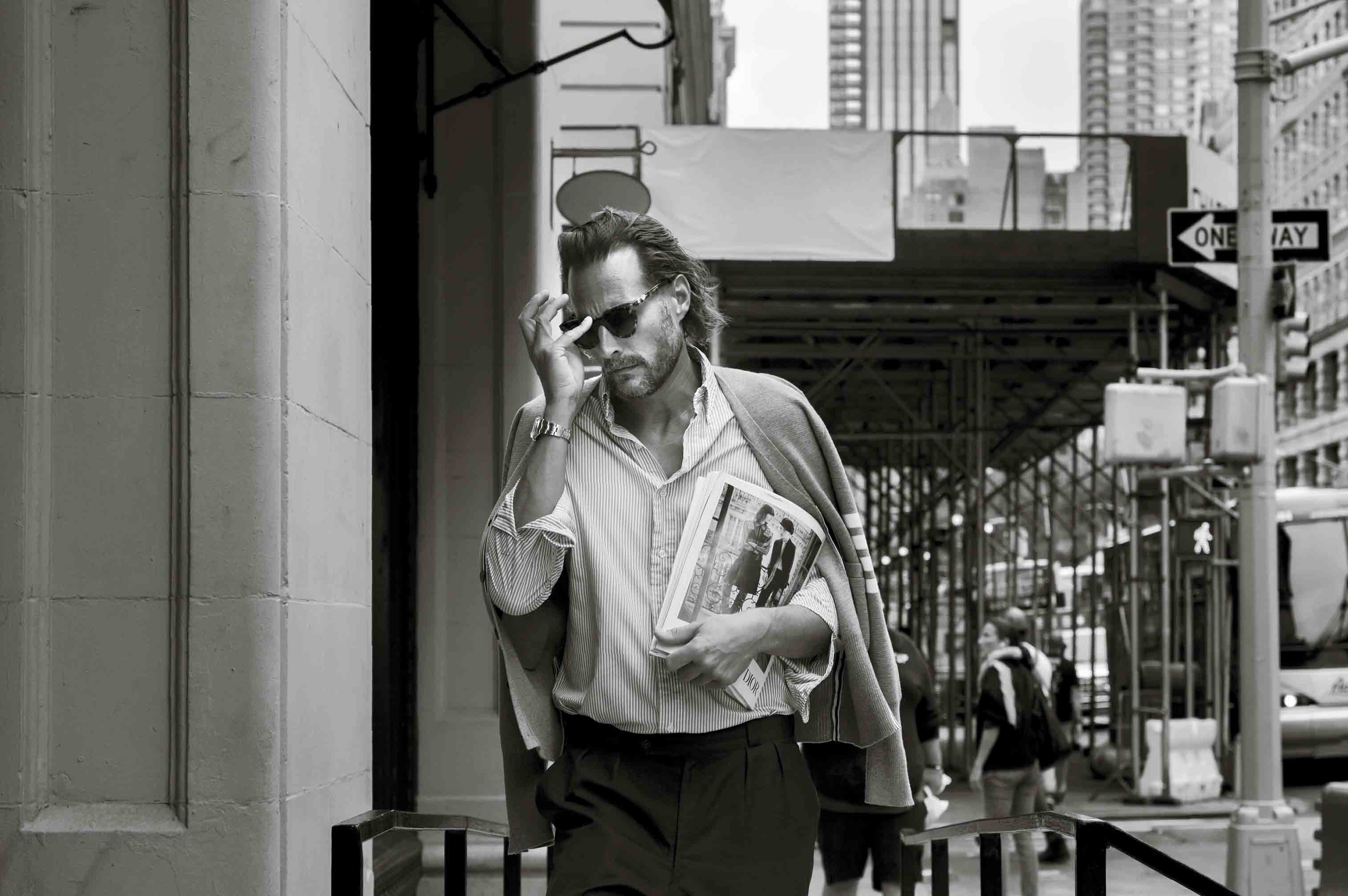

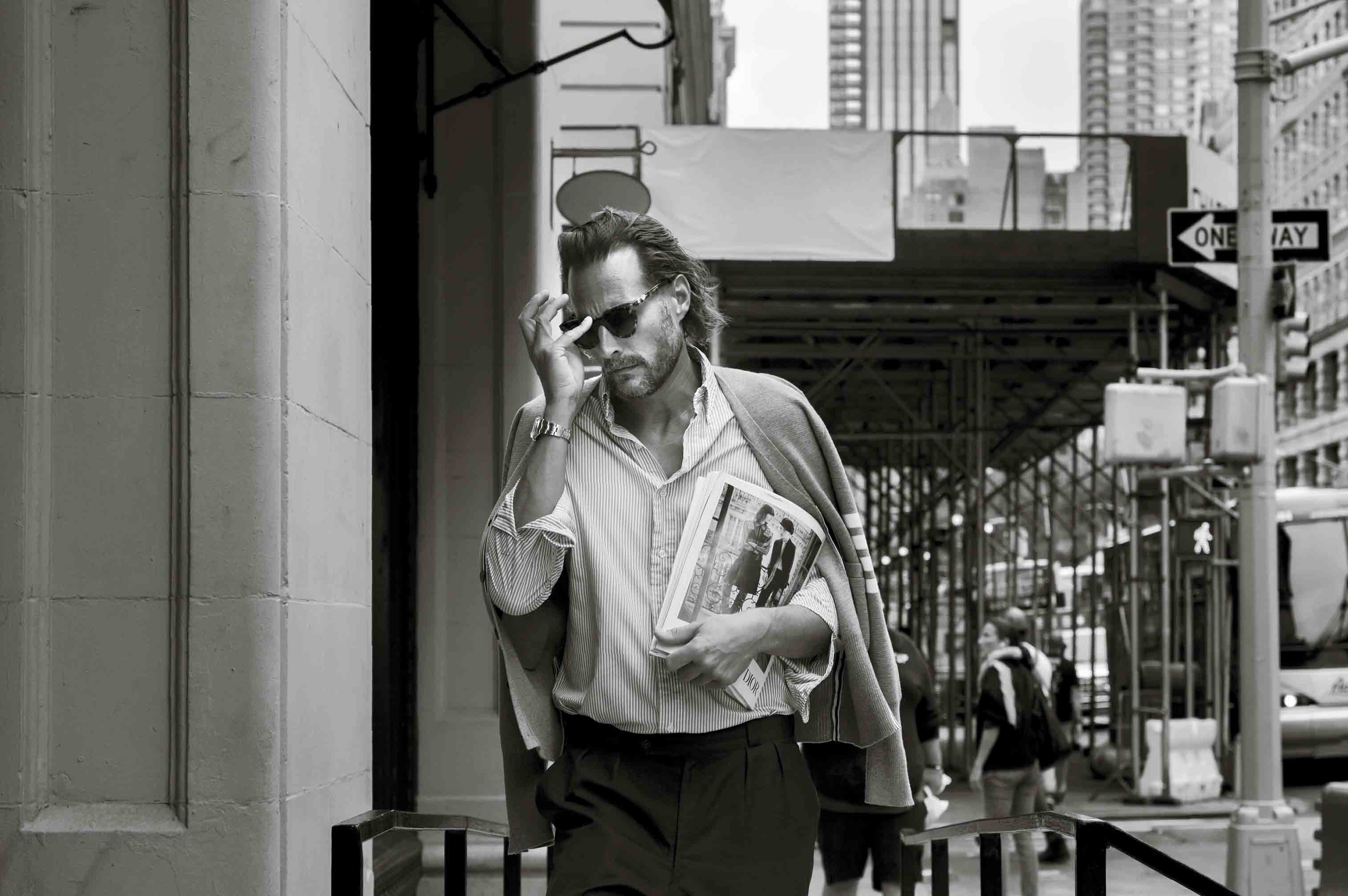

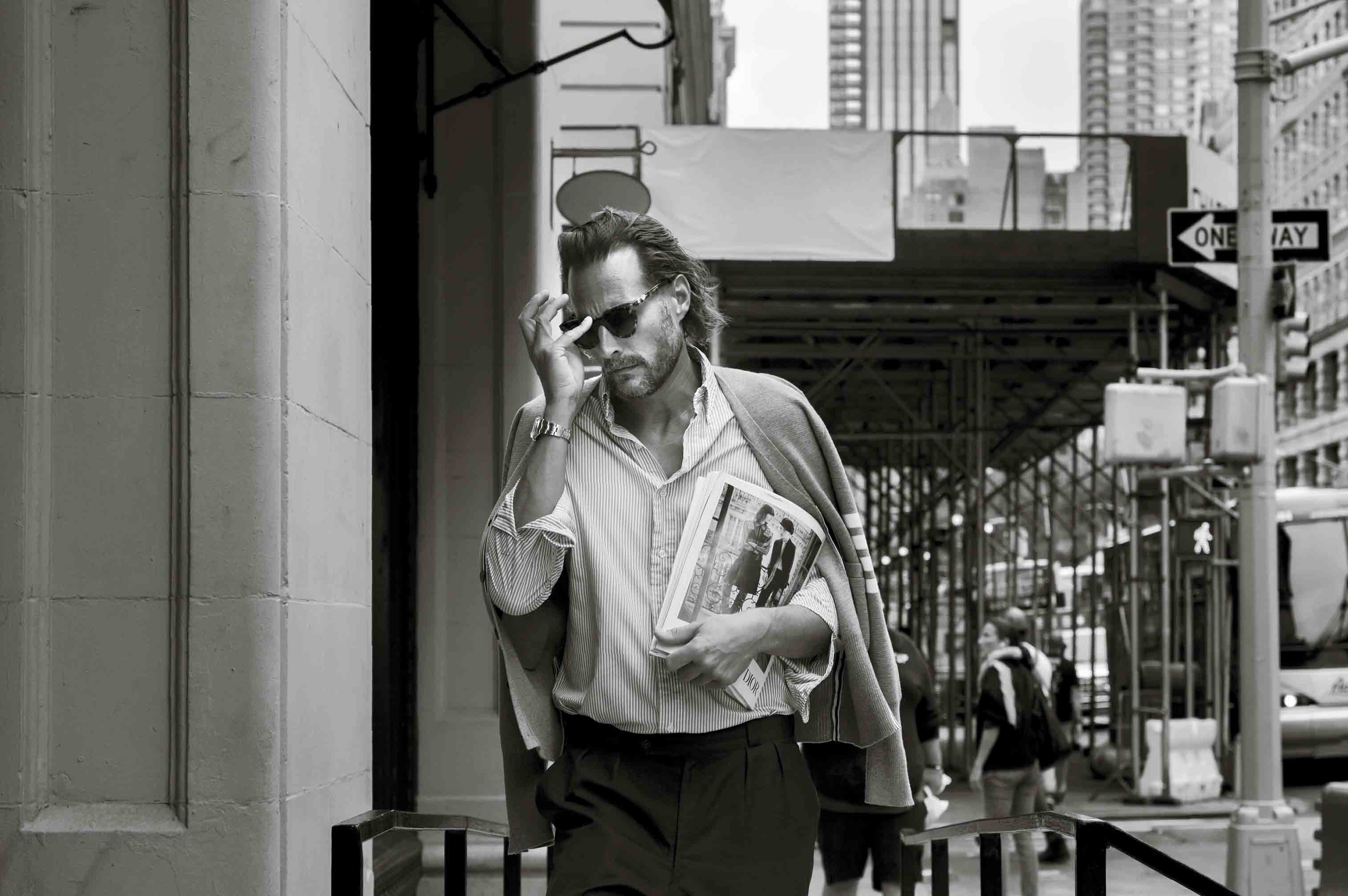

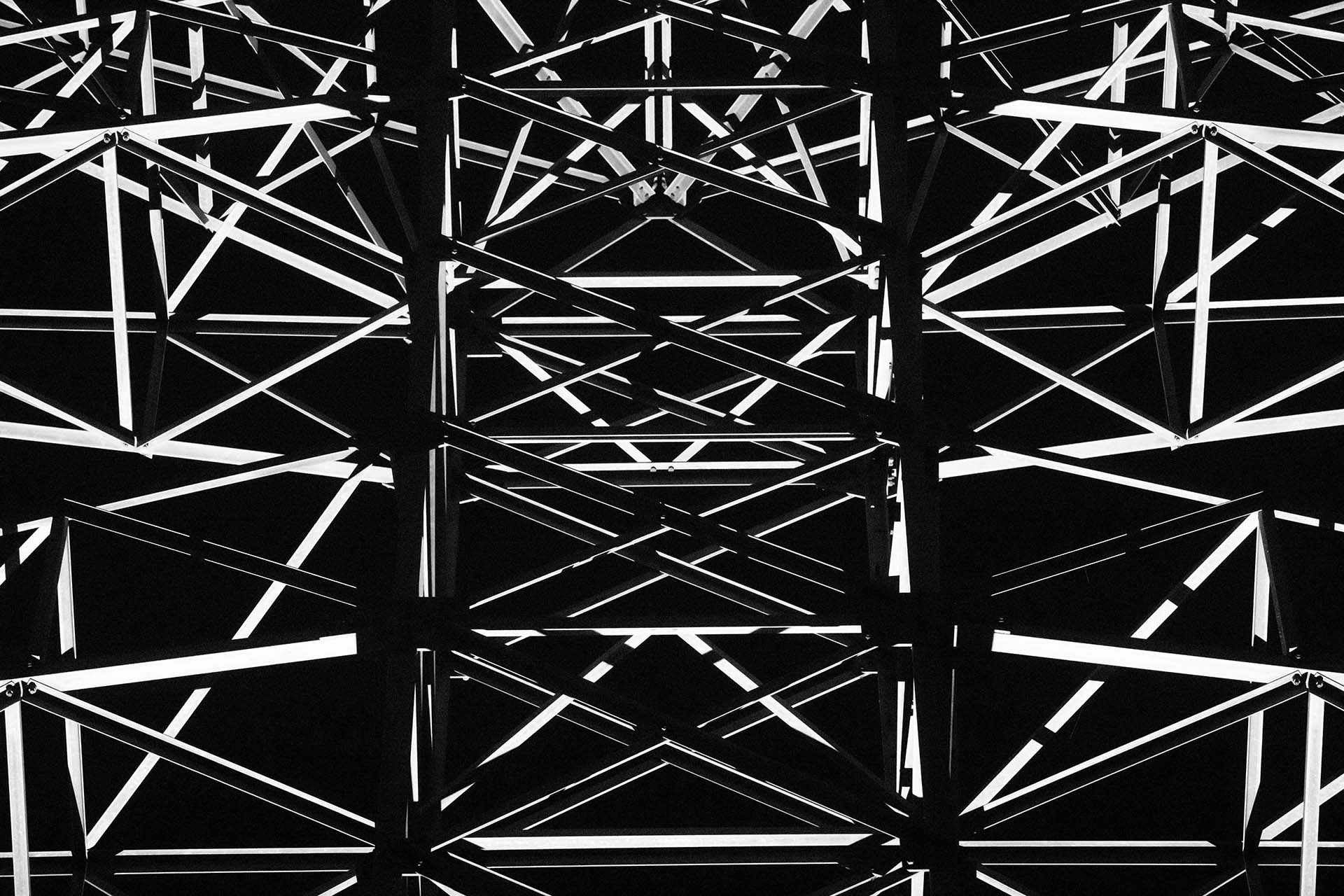

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

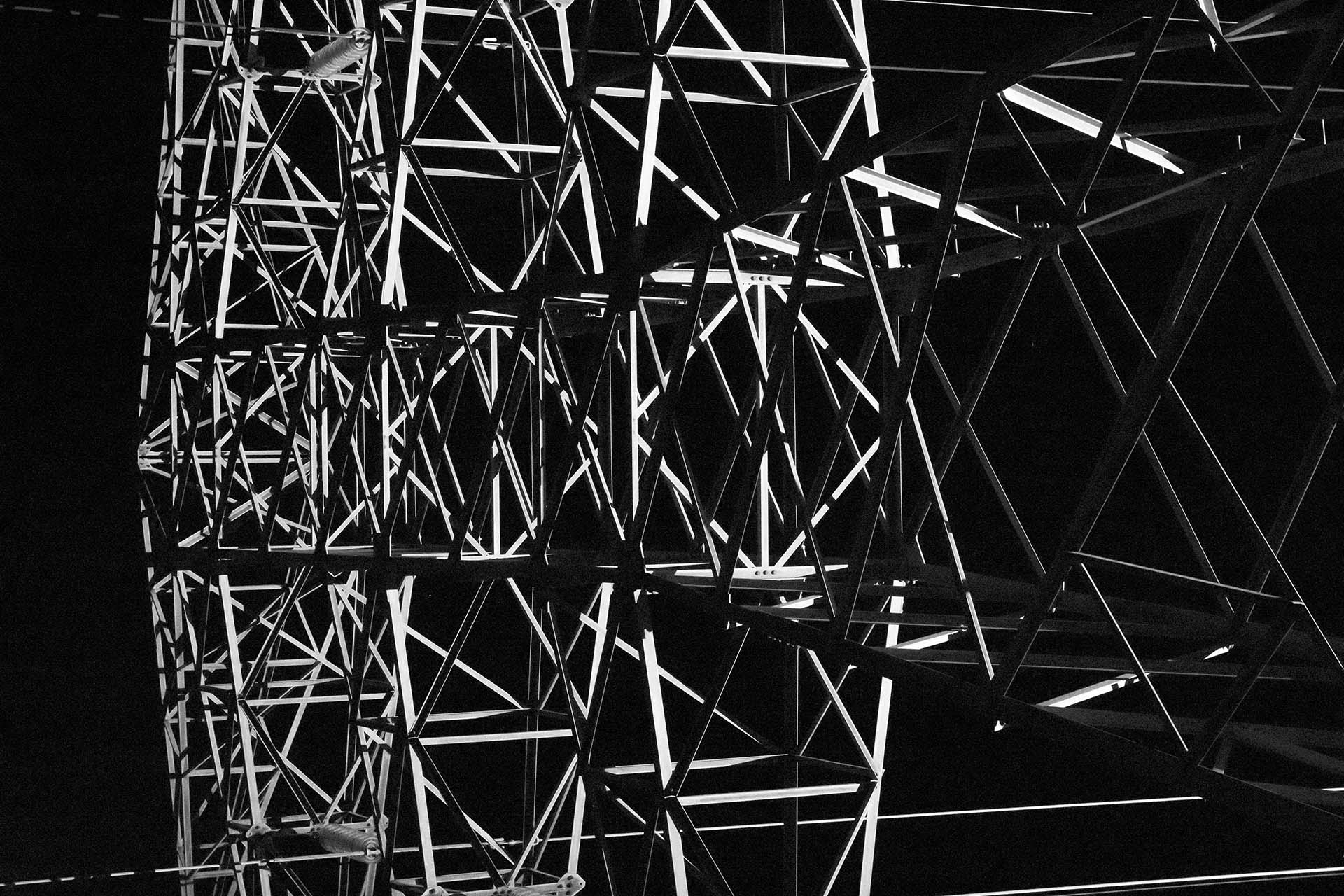

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

(2020-ongoing)

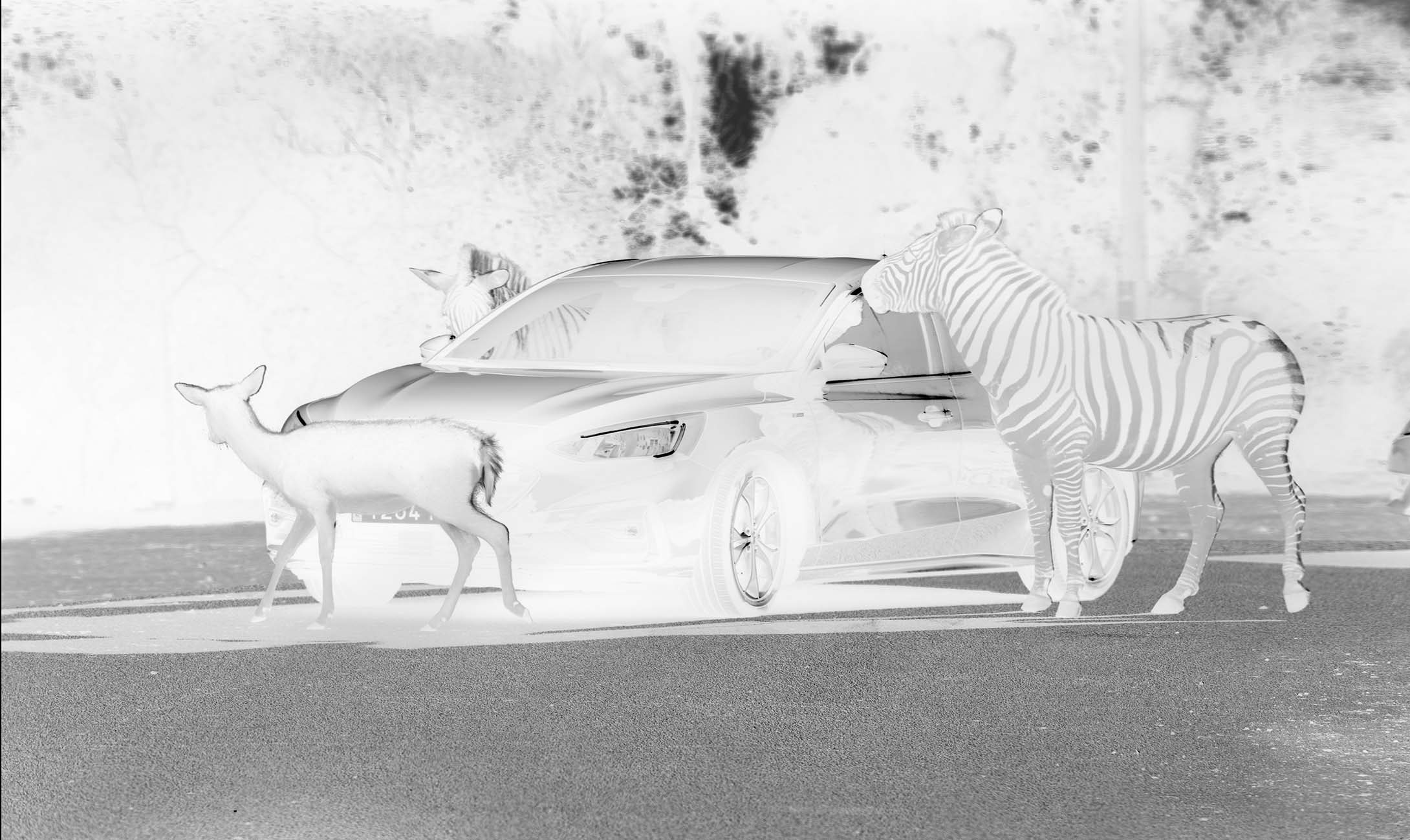

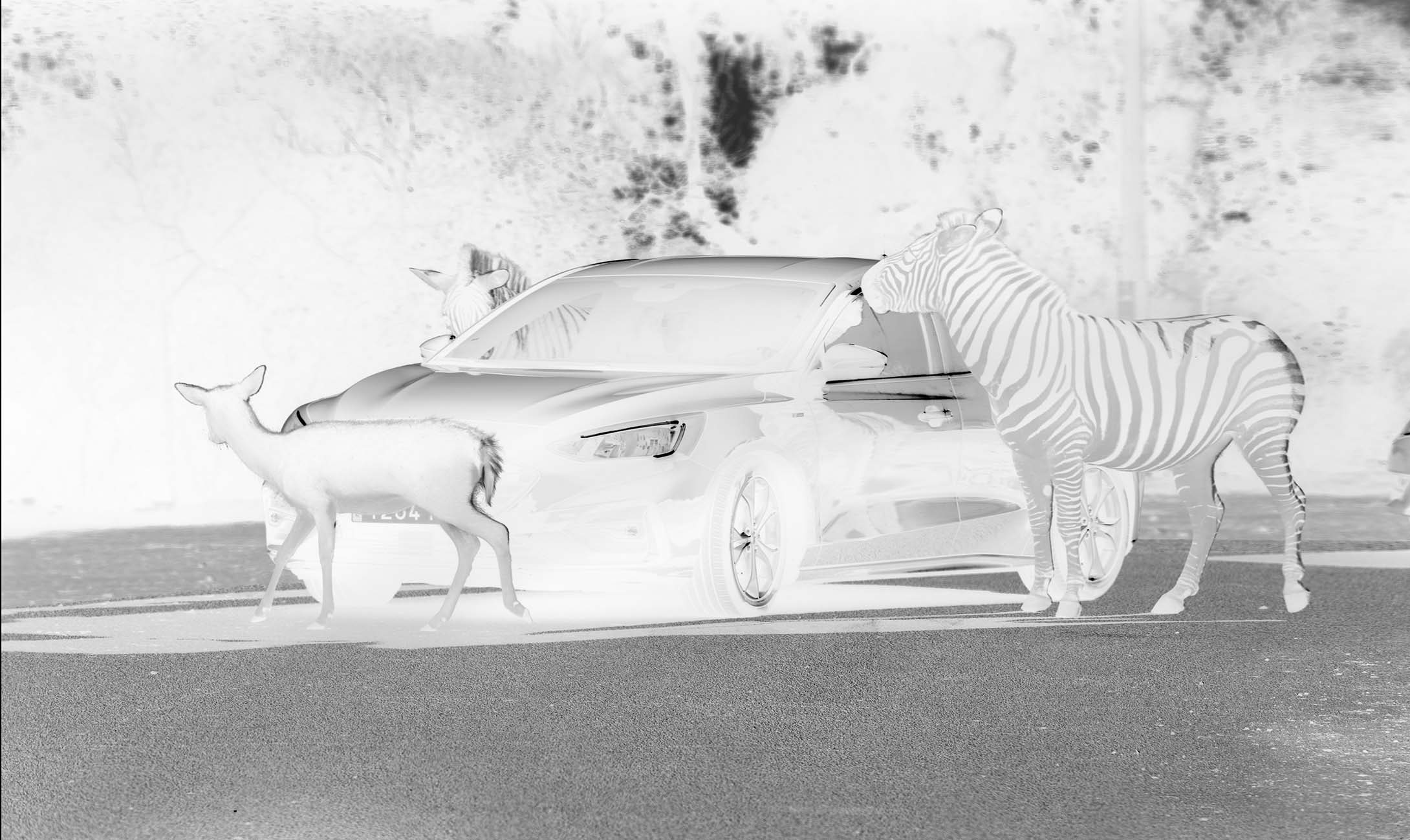

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

(2020-ongoing)

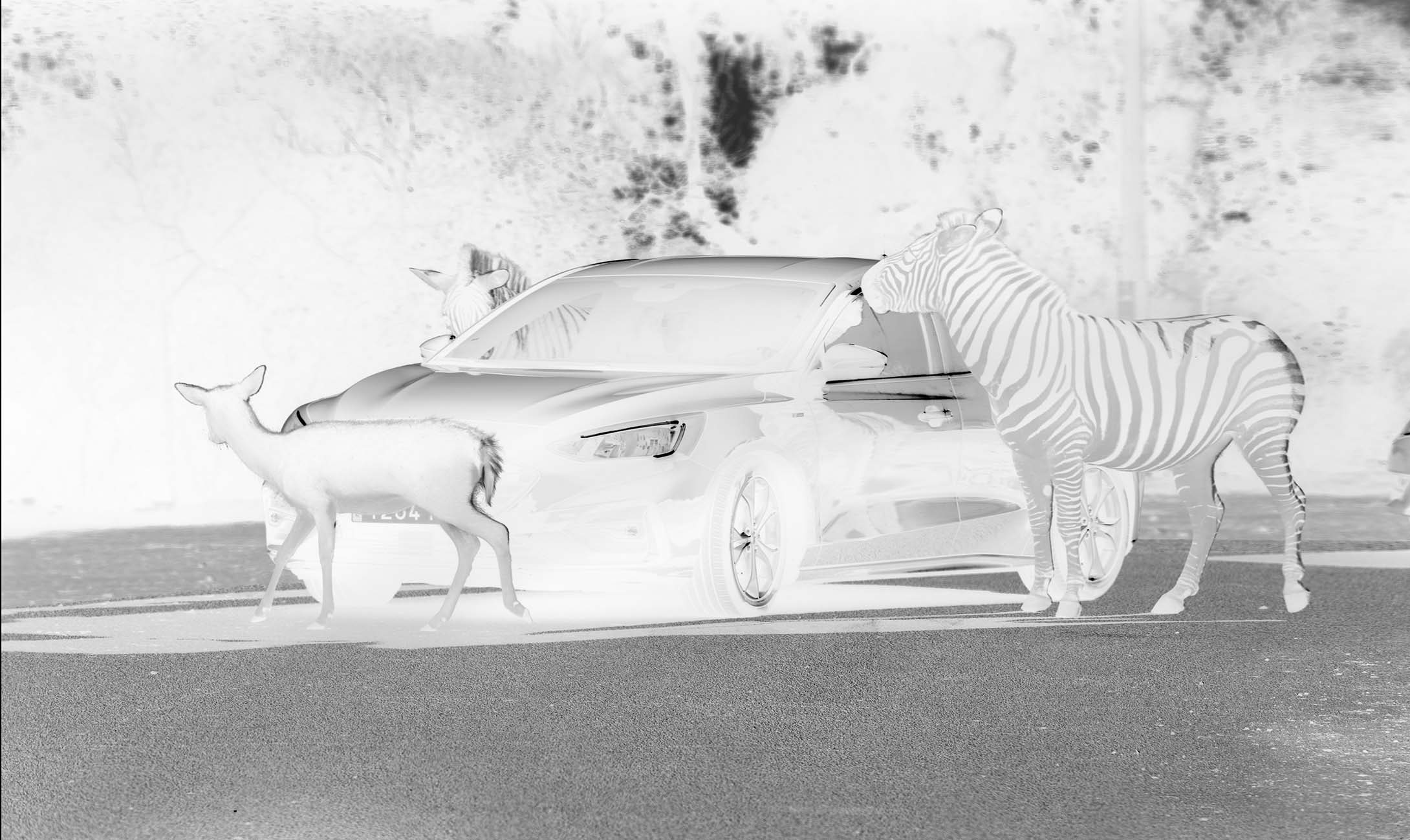

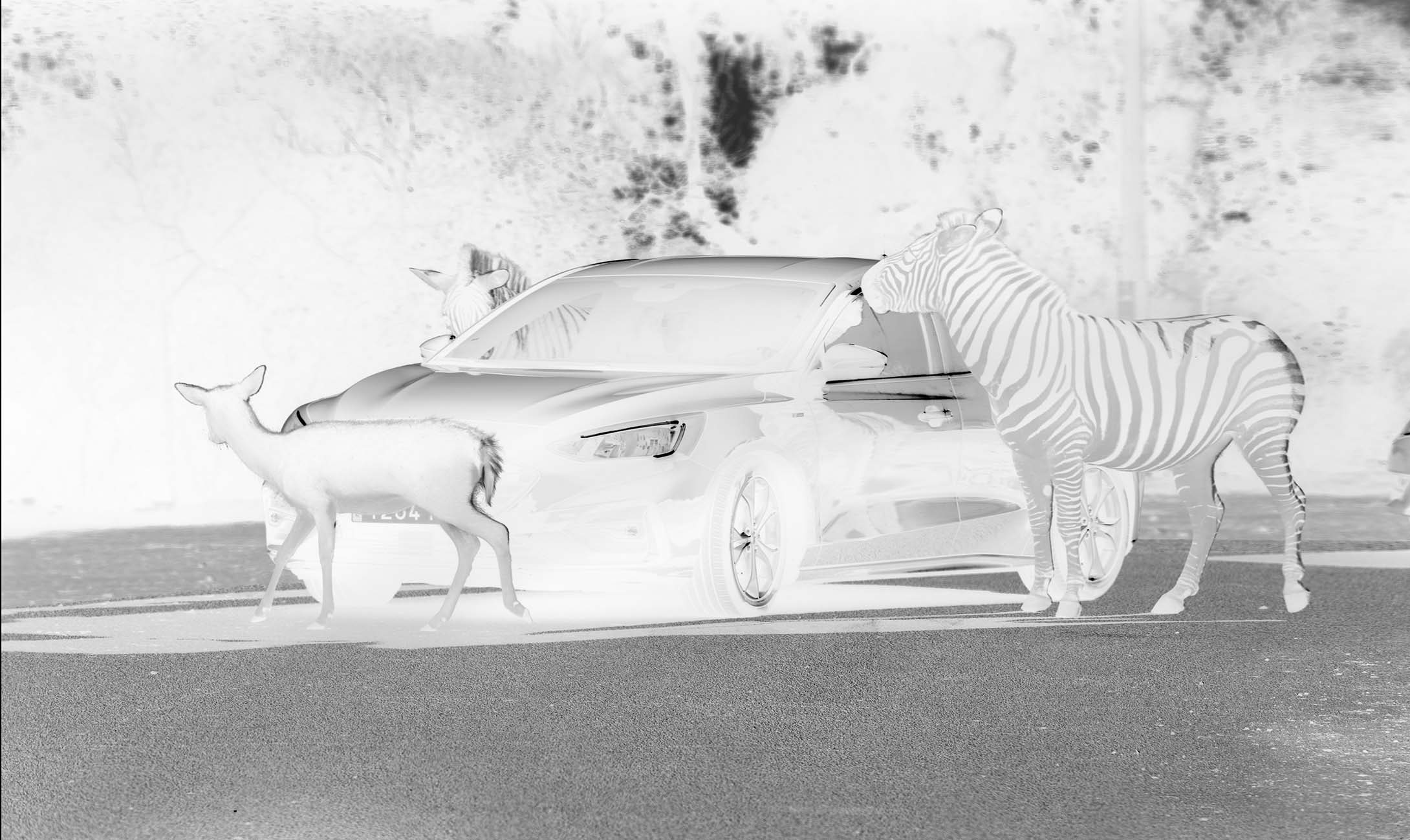

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

(2020-ongoing)

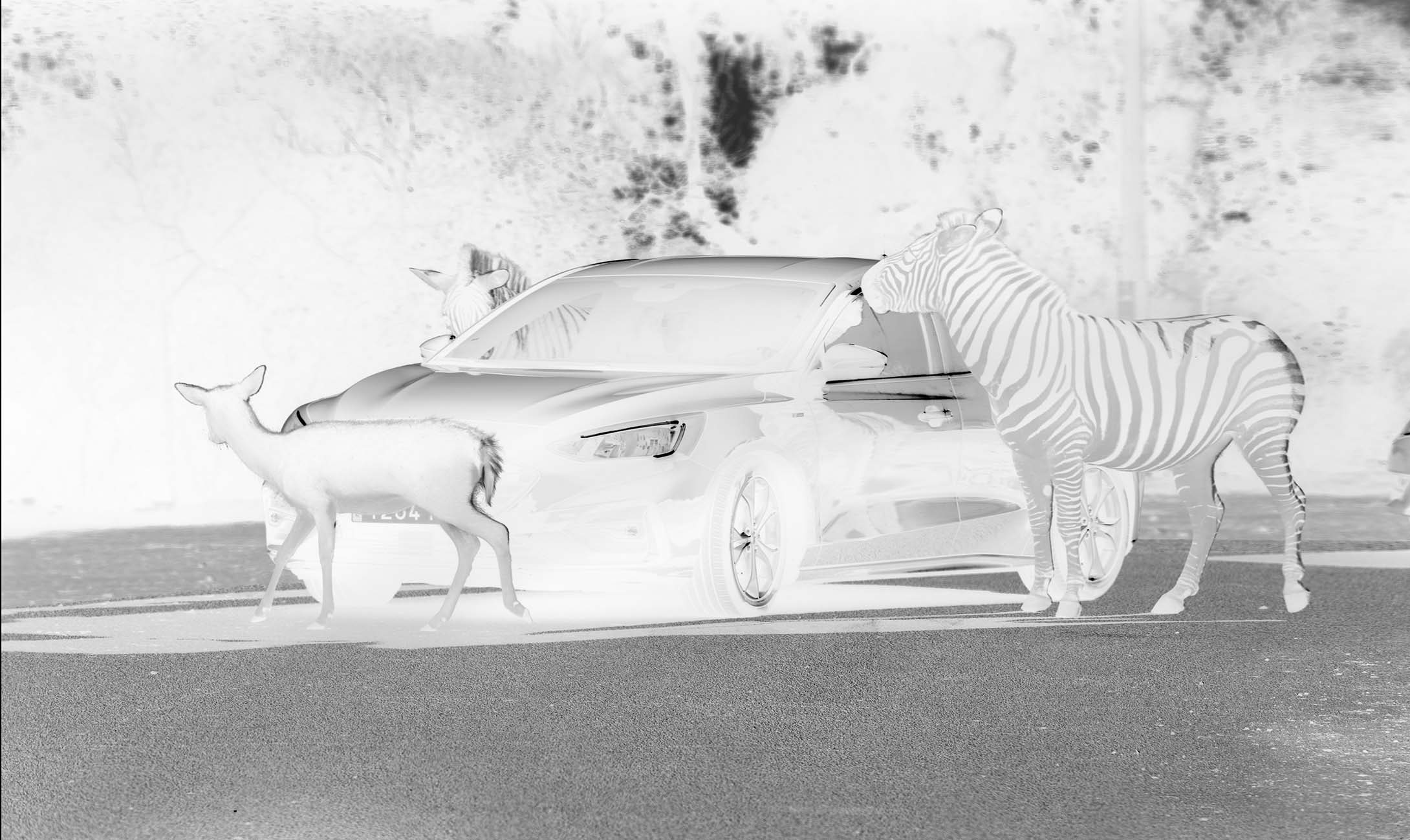

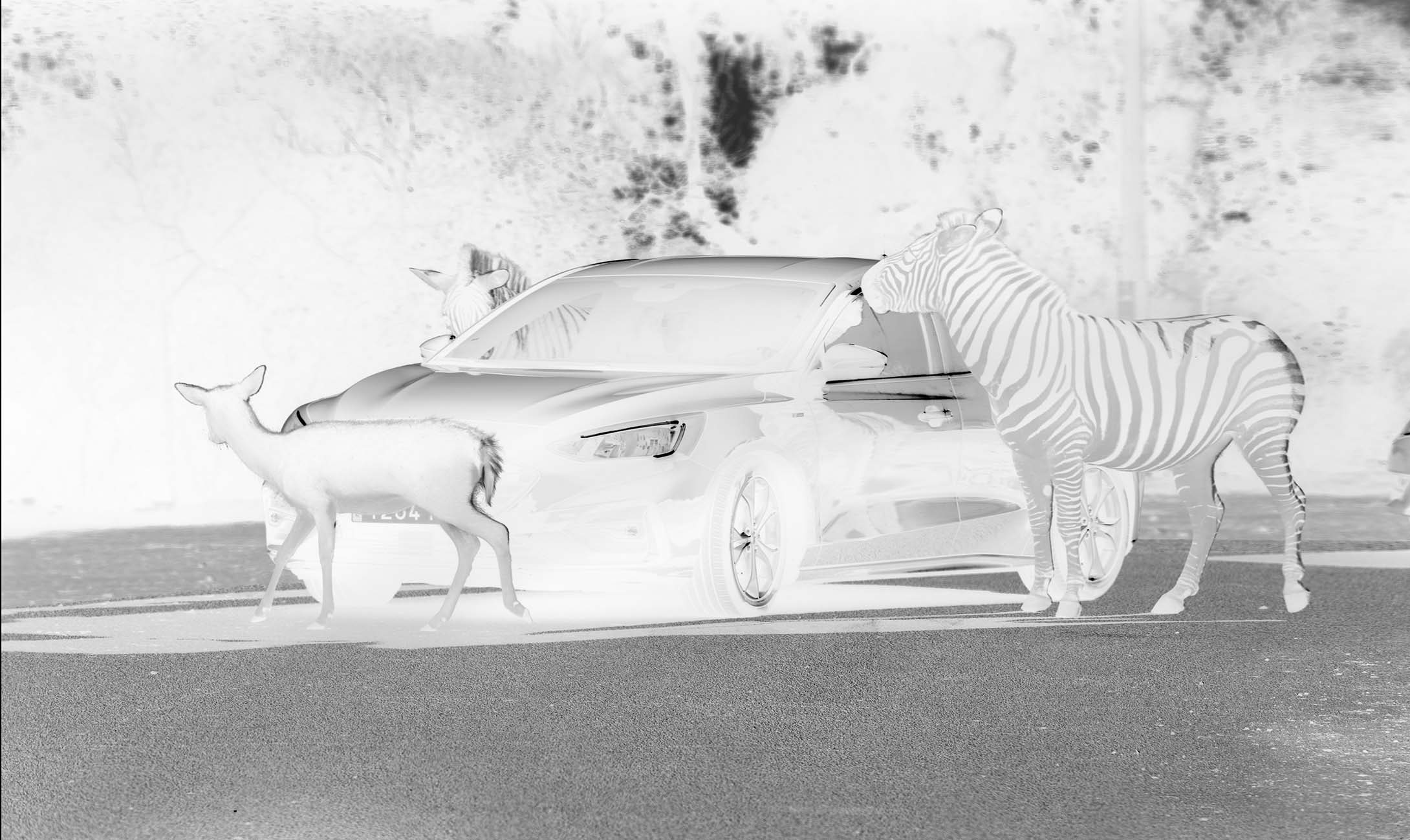

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

(2020-ongoing)

ARTHUR LARRUE SUMER

ARTHUR LARRUE SUMER

ARTHUR LARRUE SUMER

ARTHUR LARRUE SUMER

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them,

that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

Arthur Larrue Sumer

(extract)

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them,

that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

Arthur Larrue Sumer

(extract)

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

PUSH POWER ( A 1 ) visualizer for Actress´s single from LXXXVIII album, released on Ninja Tune ( 2023 )

PUSH POWER ( A 1 ) visualizer for Actress´s single

from LXXXVIII album, released on Ninja Tune

PUSH POWER ( A 1 ) visualizer for Actress´s single

from LXXXVIII album, released on Ninja Tune

ORDER

ORDER

ORDER

ORDER

Regard sur la nouvelle scéne photographique spagnole. LE BAL. Paris, 2014.

Regard sur la nouvelle scéne

photographique spagnole. LE BAL. Paris, 2014.

Regard sur la nouvelle scéne photographique spagnole

LE BAL. Paris, 2014

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt) Watch full version

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt) Watch full version

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt)

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

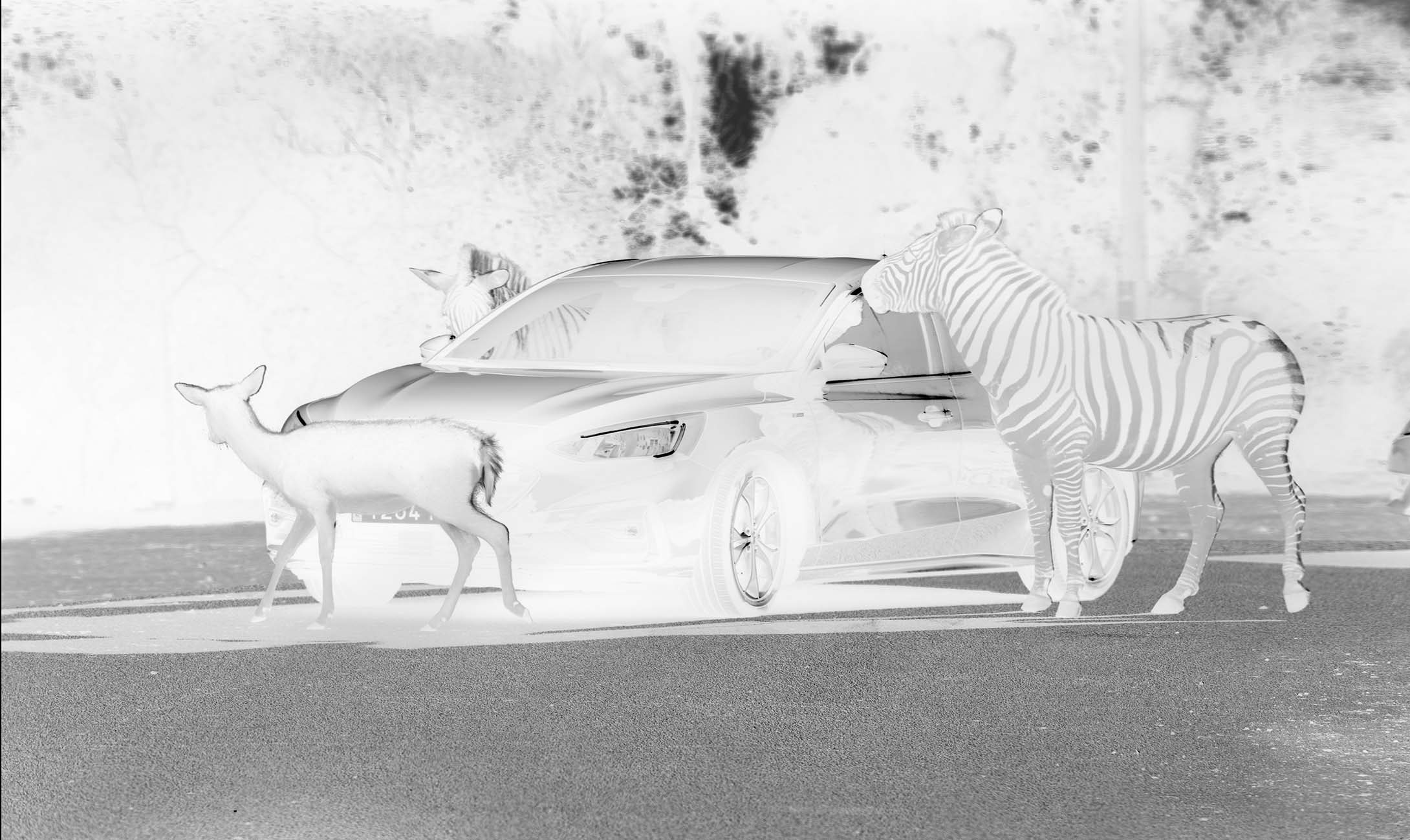

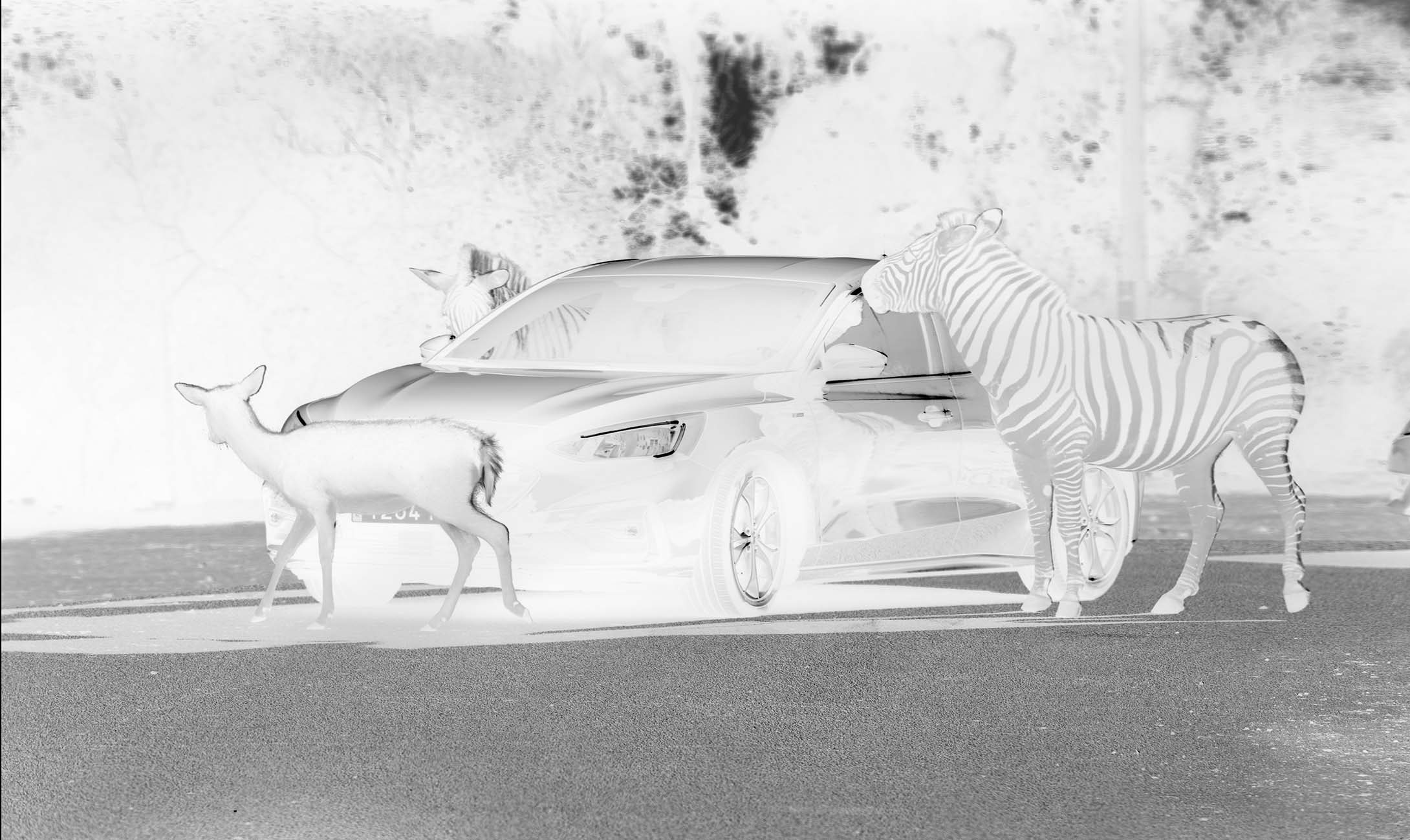

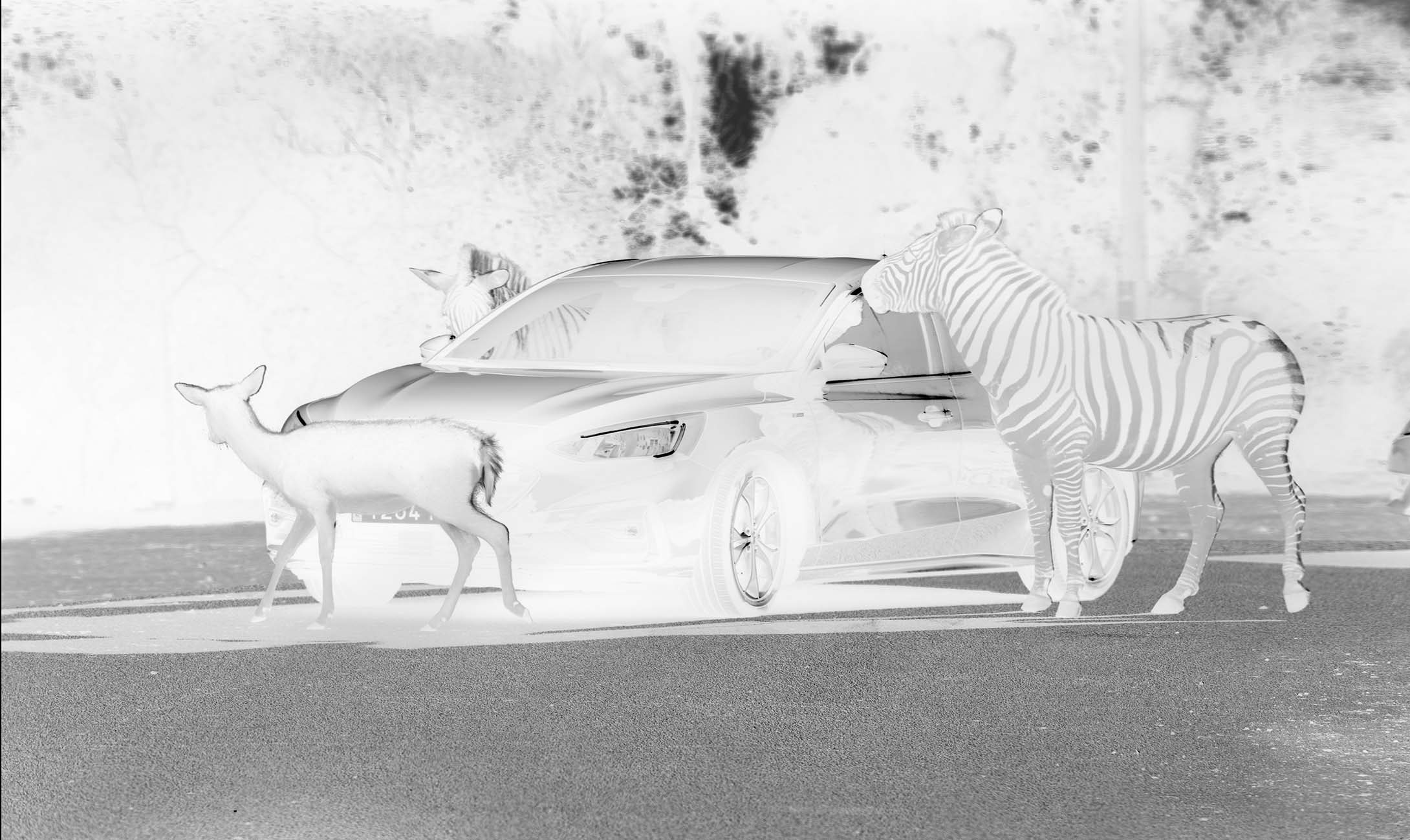

AUTOPHOTO Fondation Cartier

pour l´art aontemporain. Paris, 2017.

AUTOPHOTO. Fondation Cartier pour l´art contemporain. Paris, 2017.

AUTOPHOTO. Fondation Cartier pour l´art contemporain. Paris, 2017.

AUTOPHOTO. Fondation Cartier pour l´art contemporain. Paris, 2017.

KARMA. Fresh Gallery. Madrid, 2014

KARMA

Fresh Gallery. Madrid, 2014.

KARMA

Fresh Gallery. Madrid, 2014

KARMA

KARMA

KARMA

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt)

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt)

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

KARMA audiovisual (excerpt)

Video and music: Óscar Monzón

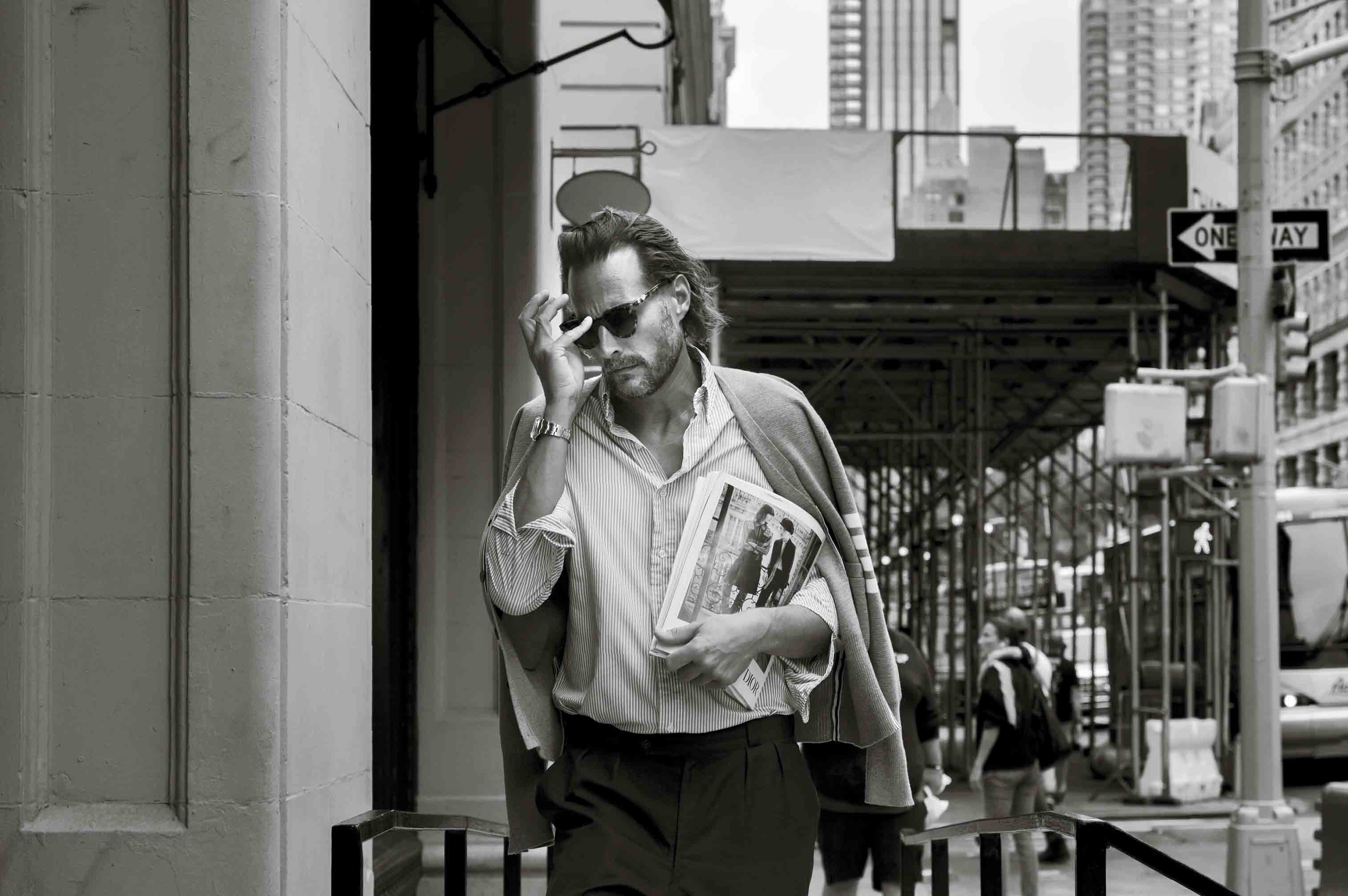

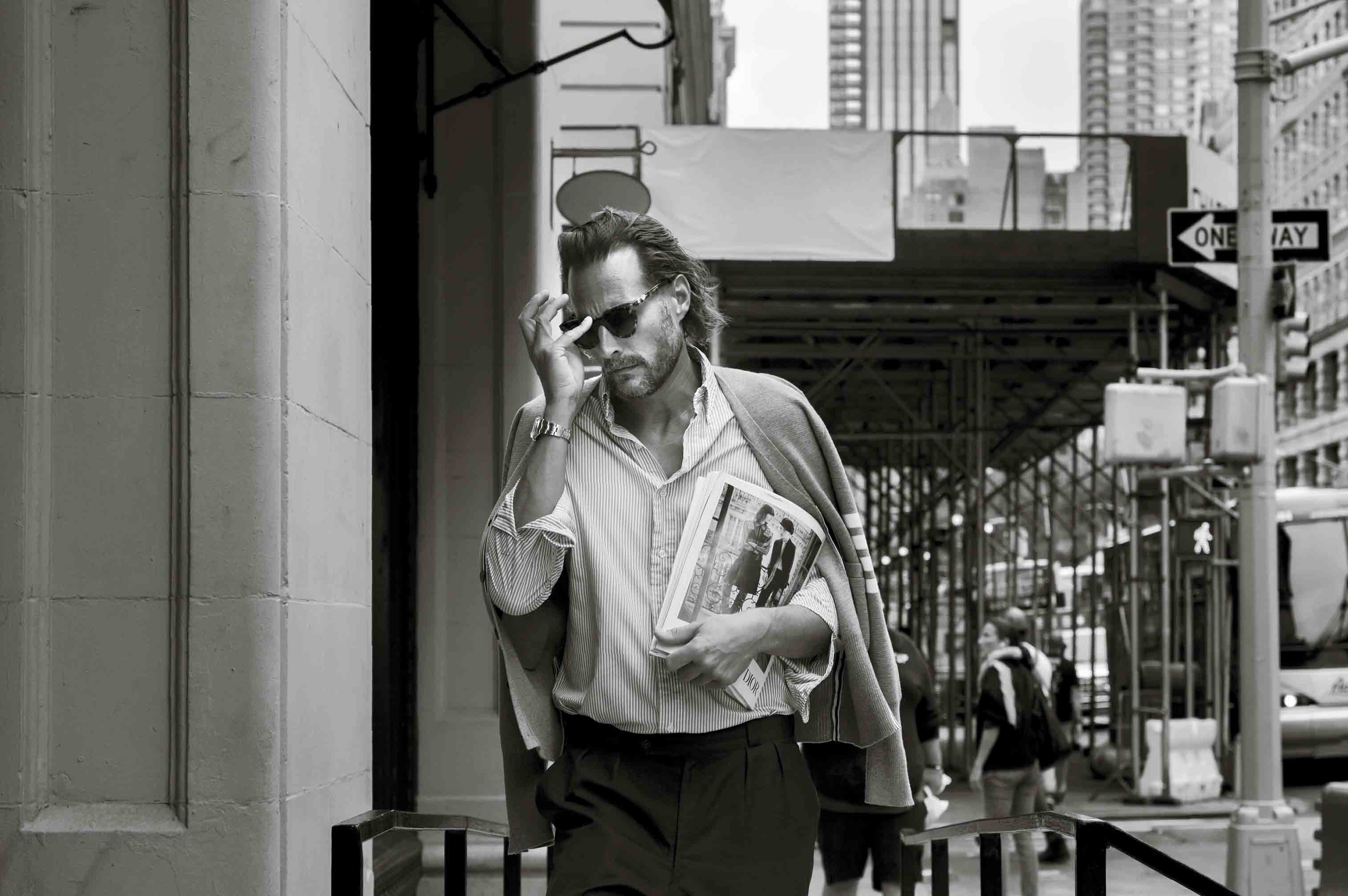

Óscar Monzón is a photographer, video and sound artist born in Málaga (Spain) in 1981.

He studied photography at Artediez School in Madrid (1999–2001) and, after co-founding and being an active member of the Blank Paper collective (2003–2017), has developed a body of work that has been exhibited at institutions such as IvoryPress, Círculo de Bellas Artes, and Institut Français in Madrid; Fundación Foto Colectania in Barcelona; Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Le BAL in Paris; IMA Gallery in Tokyo; as well as in international festivals including Les Rencontres d’Arles (France), Breda Photo (Netherlands), Lianzhou Photo (China), and PhotoEspaña.

He has been awarded a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Culture for the College d ́Espagne in Paris, the Paris Photo/Aperture Foundation First Book Award, and the First Prize of the MAST Grant on Industry and Work from the Fondazione MAST in Bologna.

Monzón has published four books: KARMA (RVB Books, Dalpine, 2013), ÉXTASIS (Dalpine, 2017), ORDER (RVB Books, 2021) and SUMER (next 2026).

Óscar Monzón is a photographer, video and sound artist born in Málaga (Spain) in 1981.

He studied photography at Artediez School in Madrid (1999–2001) and, after co-founding and being an active member of the Blank Paper collective (2003–2017), has developed a body of work that has been exhibited at institutions such as IvoryPress, Círculo de Bellas Artes, and Institut Français in Madrid; Fundación Foto Colectania in Barcelona; Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Le BAL in Paris; IMA Gallery in Tokyo; as well as in international festivals including

Les Rencontres d’Arles (France), Breda Photo (Netherlands), Lianzhou Photo (China), and PhotoEspaña (Spain).

He has been awarded a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Culture for the College d ́Espagne in Paris, the ParisPhoto/Aperture Foundation First Book Award, and the First Prize of the MAST Grant on Industry and Work from the Fondazione MAST in Bologna.

Monzón has published four books: KARMA (RVB Books, Dalpine, 2013), ÉXTASIS (Dalpine, 2017), ORDER (RVB Books, 2021) and SUMER (RVB Books, forthcoming 2026).

SUMER

short film

( fragment )

Script: Arthur Larrue

Video, sound: Óscar Monzón

Voice: Victoire de Lencquesaing

SUMER

short film

( fragment )

Script: Arthur Larrue

Video, sound: Óscar Monzón

Voice: Victoire de Lencquesaing

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

‘ You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

(2020-ongoing)

ARTHUR LARRUE SUMER

At the sight of the new photograph, Gabrielle seemed puzzled at first. Having put down the Steyr, she took off her mask and other gear to make herself more comfortable. She pulled her hair back and tied it into a ponytail with an elastic band. Her small grey eyes went from one headlight to another, from one metal or LED lettering to another. The part of Óscar’s refuge they were in was plastered with similar photographs. Among them, Gabrielle was looking for repetitions of shapes, crossings of lines that might be identical, similar intensities of light. She pried some of the photographs off the walls to examine them more closely, comparing one with another. Like Sumerian graphemes, the light patterns on the headlights were based on more or less minimal, more or less identifiable interlocking lines. Her approach to headlights was not exactly the same as Óscar’s, perhaps even the opposite: there was no aesthetic notion involved, no space for dreaming. In a way, she was deciphering the mystery he was savouring.

You’re the one who knows how to read headlights,’ Óscar told Gabrielle.

‘Yes, you only know how to look at them.’

‘Look at them, yes. And then take a photo of them, that’s all.’

‘Suffer or act, you suffer and I act. You see, I can read.’

‘Whatever, Gaby. No problem for me. You act, you read. Whatever you want.’

In the meantime, he had finished rolling the joint. She hadn’t taken her eyes off the pictures.

Six thousand five hundred years ago, the inhabitants of the first Sumer had begun to read and write by trying to decipher the tracks made by birds in the sand of the far south of ancient Mesopotamia. They thought that these birds, having descended from the sky, must have been messengers of the gods, and that their footprints were coded messages. Hence, from the jumble of their footprints and by cataloguing this mess of tangled lines, crosses and stripes, they created cuneiform writing. They wrote it on clay tablets, engraved their laws on steles and composed songs. They hadn’t managed to understand the chaos of the gods better, but they had achieved two of the most decisive advances in human history, indeed the only two discoveries that truly deserved to be called ‘historic’ insofar as they had, among all others, begun history: reading and writing.

(Extract)

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue ( 2020 - ongoing )

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue

SUMER Óscar Monzón & Arthur Larrue